Components

Modules are groups of related code, but architects often focus on components, which are the physical versions of modules. These components are packaged differently depending on the programming language, such as jar files in Java or DLLs in .NET.

Component Scope

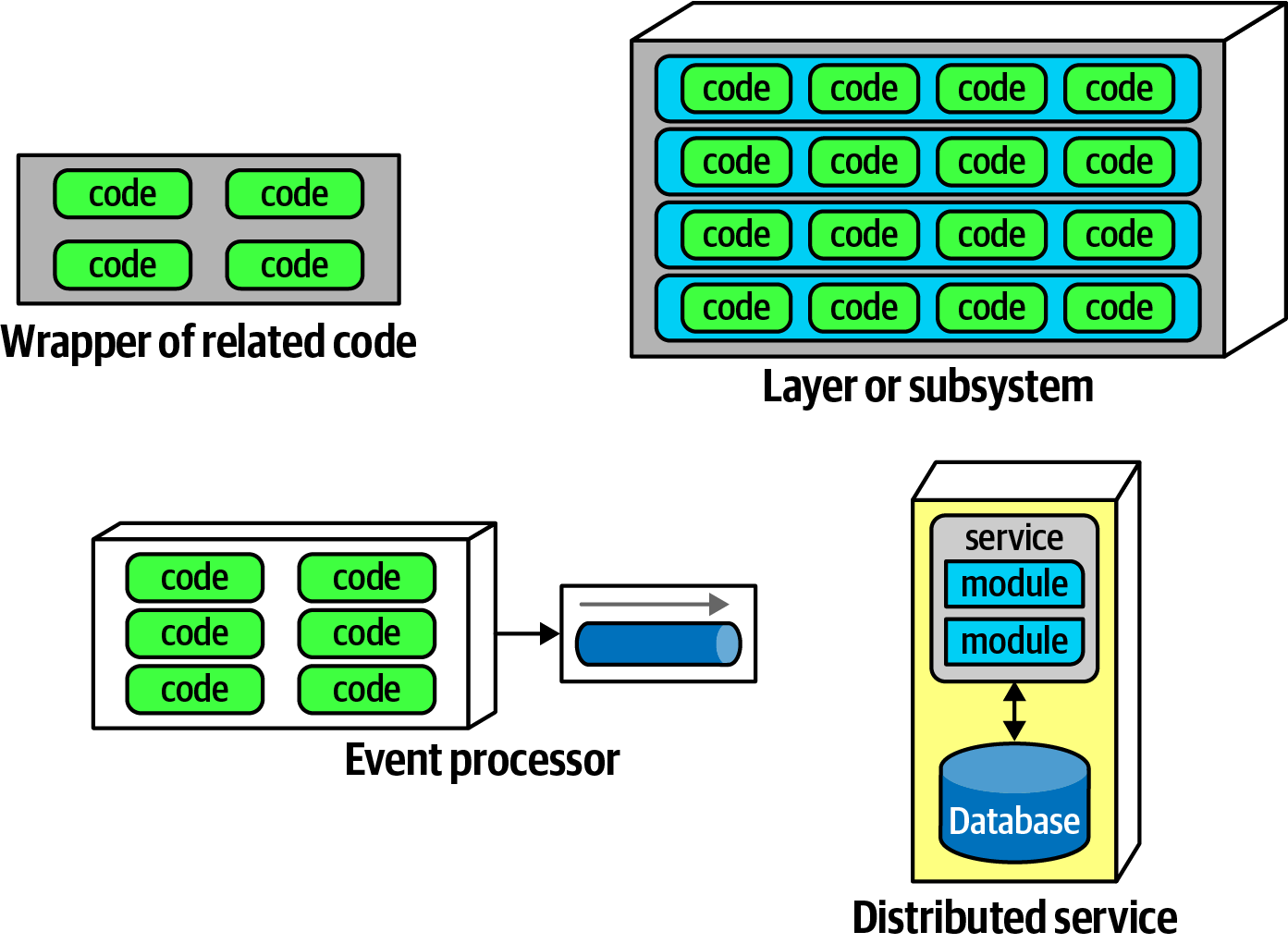

Components provide a language-specific way to group artifacts together, often by nesting them to create layers. It's helpful to divide the concept of components as shown in the image below.

Different varieties of components from Fundamentals of Software Architecture.

Wrapper of Related Code

The simplest form of a component is one that wraps code at a higher level of modularity than classes or functions. This is often referred to as a library. Libraries typically run in the same memory address as the calling code and communicate via language function call mechanisms. Libraries are usually compile-time dependencies.

Layer or Subsystem & Event Processor

Components can also take the form of subsystems or layers within an architecture, serving as the deployable units of work for many event processors.

Distributed Service

Distributed services tend to run in their own separate address spaces and communicate using low-level networking protocols like TCP/IP or higher-level formats like REST or message queues. They are stand-alone and deployable units in architectures such as microservices.

Components are the basic building blocks in architecture and are a crucial consideration for architects. One of the key decisions architects must make is how to divide the architecture into top-level components. While architects are not obligated to use components, they often find them beneficial as they provide a higher level of modularity.

Architect Role

The architect typically plays a central role in defining, refining, managing, and overseeing components within an architecture. This work is done in collaboration with various stakeholders, including business analysts, subject matter experts, developers, QA engineers, operations teams, and enterprise architects, to create the initial software design.

In most cases, components represent the lowest level of the software system that an architect directly interacts with. These components are composed of classes or functions, depending on the implementation platform. The detailed design of these classes or functions often falls under the responsibility of tech leads or developers. While architects may involve themselves in class design, especially when applying design patterns, they should avoid micromanaging every decision throughout the system. Allowing other roles to make significant decisions is essential for empowering the next generation of architects.

One of the architect's initial tasks on a new project is to identify components. However, before doing so, architects must have a clear understanding of how to partition the overall architecture effectively.

Architecture Partitioning

In software architecture, there are always trade-offs to consider, including how architects design components within an architecture. Components serve as general containers, allowing architects to structure the system as they see fit. There are several common styles available, each with its own set of trade-offs to consider.

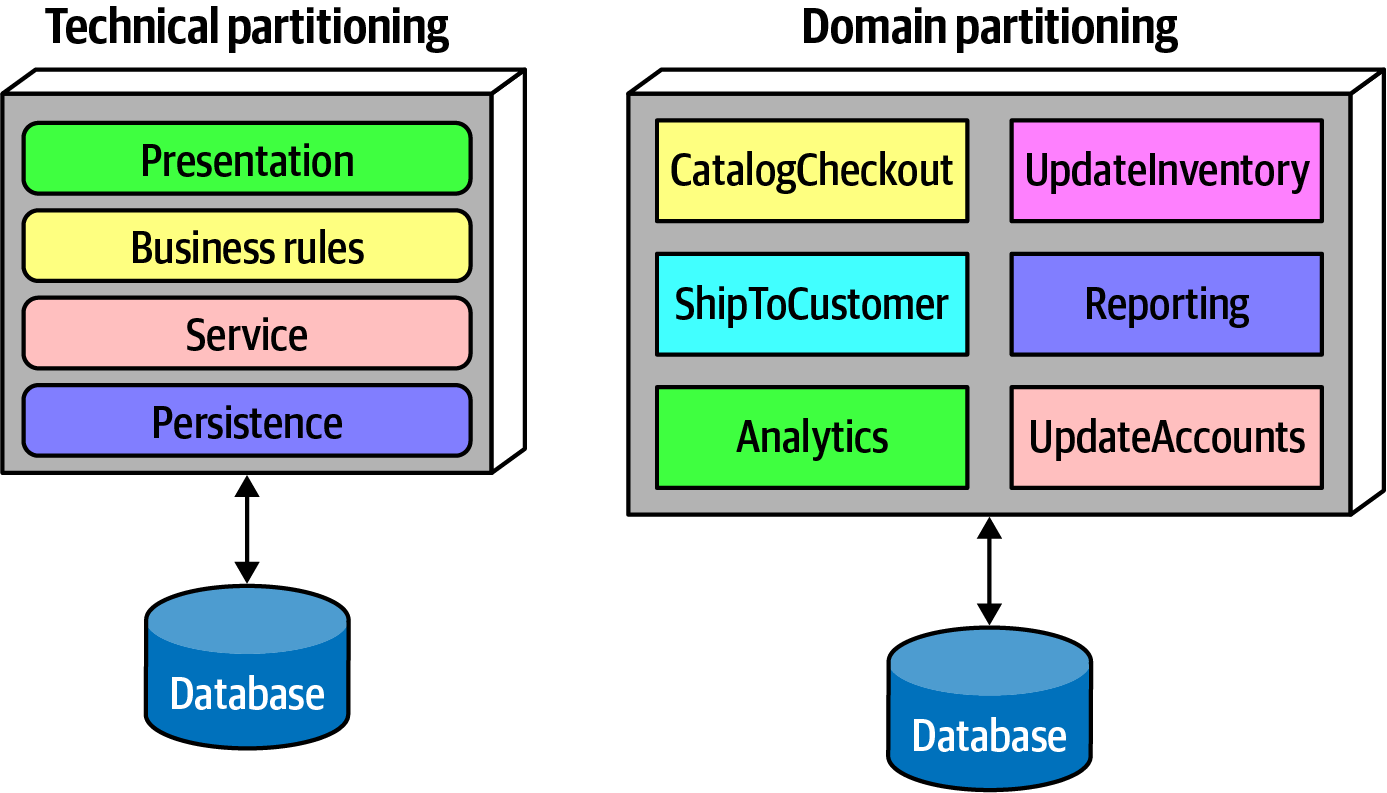

Let's consider two common architecture styles shown below.

Two types of top-level architecture partitioning: layered and modular from Fundamentals of Software Architecture.

Technical Partitioning as a version of Layer Monolith

In the layer monolith, the architecture is divided into layers each with specific responsibilities.

Domain Partitioning as a version of Modular Monolith

In the modular monolith, organized around domains or business functionalities

It's important to note that in each of these variations, the top-level components (layers or components) often contain embedded sub-components. The choice of top-level partitioning is a critical decision for architects, as it defines the fundamental architecture style and the way code is organized.

Technical Partitioning

When organizing a codebase through technical partitioning, code is grouped based on its technical aspects. For instance, code responsible for interacting with a database is placed in the persistence layer. This approach ensures that code with similar technical concerns resides within a single layer of the architecture.

Model-View-Controller (MVC)

One classic example of this approach is the Model-View-Controller (MVC) design pattern. MVC separates code into distinct components, including the model (data and logic), view (user interface), and controller (intermediary between model and view). This separation simplifies code organization and enhances comprehensibility.

In technical partitioning, a key principle is to separate technical concerns. This separation results in different levels of decoupling. For instance, if we consider the service layer, it's primarily connected to the persistence layer below it and the business rules layer above it. This means that any changes made to the persistence layer will likely only impact these adjacent layers.

This partitioning style is valuable because it minimizes the potential for changes in one part of the system to create significant impacts on other components. It helps reduce the cascading effects of modifications on dependent parts of the architecture.

In layered architecture, there's an interesting impact on how companies organize their project teams. It often leads to a situation where backend developers work together in one department, database administrators (DBAs) in another, and the presentation team in yet another department.

Domain Partitioning

Another way to structure architecture is through domain partitioning, which is inspired by the Domain-Driven Design (DDD) approach. In DDD, architects identify separate and independent domains or workflows within a complex software system. While each of these domains may have its own layers, such as a business rules layer and its own persistence library, the main focus of domain partitioning is on these separate domains. For instance, CatalogCheckout represents a specific domain within your system. And may have a diffent persistence library than others components.This approach aligns well with how changes typically happen in projects.

In a technically layered architecture, a common business workflow like CatalogCheckout is spread across multiple layers, with code related to it present in each layer. However, in domain partitioning, CatalogCheckout's code is concentrated within its own sub-component, resulting in a more focused and organized structure.

Developer Role

Developers often work with components that have been collaboratively designed with architects, breaking them down into classes, functions, or subcomponents. The responsibility for designing classes and functions is usually shared among architects, tech leads, and developers, with a significant portion falling on the developer's shoulders.

It's important to note that developers shouldn't consider the architect's design as final. Software design is an iterative process, and the initial design should be seen as a starting point. During implementation, more details and refinements may emerge, leading to improvements in the design.

Component Identification Flow

Identifying components is best achieved through an iterative process that generates candidates and refines them based on feedback. The following stages outline a typical component identification workflow. In certain specialized domains, additional steps may be introduced, such as security or auditing procedures, to adapt to specific requirements.

Identifying Initial Components

In the early stages of a software project, architects face the task of determining the initial top-level components. This choice is influenced by the type of top-level partitioning they select. Beyond this, architects have the creative freedom to define components as they see fit, and then align domain functionality with these components to determine where specific behaviors should reside.

It's important to note that achieving an optimal design with this initial set of components is quite challenging. This is why architects must engage in an iterative process of component design refinement to enhance the overall system design.

Assign Requirements to Components

Once an architect has identified the initial components, the next step is to see how the project's requirements or user stories fit with these components. It might involve creating new components, consolidating existing ones, or even splitting components if they carry too much responsibility.

Remember, this doesn't have to be super precise right away. The main goal is to create a basic structure that can be adjusted and improved as the project progresses, with input from architects, tech leads, and developers.

Analyze Roles and Responsibilities

The architect also checks if the roles and responsibilities mentioned in the requirements match the component granularity. This means making sure that the way people and tasks are organized aligns with how the components are structured. Finding the right level of granularity for components can be challenging, which is why this iterative process is crucial.

Analyze Architecture Characteristics

When assigning requirements to components, architects should consider the previously identified architecture characteristics. For example, if one part of the system deals with many users simultaneously, and another part with only a few, their architectural needs will vary. While a simple approach might suggest one component for user interaction, analyzing the architecture characteristics may lead to splitting it into multiple components. This helps tailor the design to the system's specific requirements.

Restructure Components

Feedback plays a crucial role in software design. Architects must continuously refine their component design in collaboration with developers. Designing software often presents unexpected challenges, and it's impossible to anticipate every issue that may arise. Therefore, an iterative approach to component design is essential.

Firstly, it's challenging to foresee all the unique scenarios and edge cases that might require redesign. Secondly, as the architecture and development progress, a more nuanced understanding of where specific functions and responsibilities should reside emerges. This iterative process allows for a more robust and adaptable software design.

Component Design

Creating a component design involves many techniques, each with its own pros and cons. The architect's job is to analyze requirements and decide on the fundamental building blocks for the application. These techniques vary depending on the team's development process and organizational preferences.

Architects, often working with others, establish an initial component design based on their understanding of the system and their chosen approach for breaking it down, whether by technical or domain considerations. The aim is to create an initial design that divides the problem into manageable chunks while considering various architecture aspects.

Entity Trap

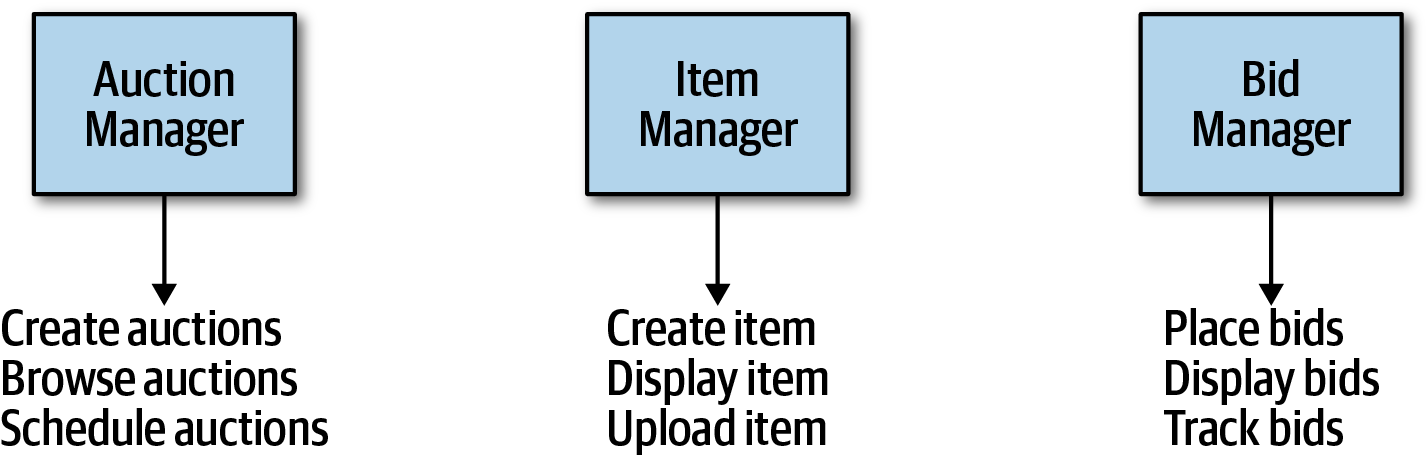

The entity trap is a common anti-pattern illustrated in the image below.

Building an architecture as an object-relational mapping from Fundamentals of Software Architecture.

It occurs when an architect creates components for each entity identified in the requirements, resembling an object-relational mapping (ORM) framework for a database. This approach is not true architecture but rather a way to handle simple database CRUD operations. ORM frameworks are available for this purpose.

The problem with the entity trap is that it inaccurately maps database relationships to application workflows, which is rarely the case in practice. This anti-pattern typically reflects a lack of consideration for the actual application workflows.

Actor/Actions Approach

The actor/actions approach is a common method that architects use to align requirements with components. In this approach, inspired by the Rational Unified Process, architects identify actors who interact with the application and define the actions these actors can perform. This approach helps discover the typical users of the system and the actions they might take.

The actor/actions approach remains popular and is effective when requirements involve distinct roles and their associated actions. This method of component design is suitable for various types of systems, whether they are monolithic or distributed.

Event Storming Approach

The event storming approach to component discovery originates from domain-driven design (DDD) and is closely associated with microservices. In event storming, the architect anticipates that the project will rely on messages and events for communication between components. To implement this, the team identifies the events that take place in the system based on requirements and identified roles. Components are then built around these event and message handlers. This approach is particularly effective in distributed architectures like microservices that heavily rely on events and messages, as it assists architects in defining the messages used in the system.

Workflow Approach

An alternative to event storming, which provides a more generic option for architects who are not utilizing domain-driven design (DDD) or messaging. In the workflow approach, components are designed around workflows, similar to event storming, but without the specific requirement of constructing a message-based system. This approach involves identifying key roles, determining the types of workflows these roles are involved in, and then creating components based on these identified activities.