Orchestration-Driven Service-Oriented Architecture

Danger

This architecture style represents an era-specific architectural style influenced by external forces and organizational philosophies. Despite its logical foundation, this architecture faced challenges that ultimately led to its downfall. It serves as a notable example of how a seemingly rational organizational idea can impede crucial aspects of the development process.

History and Philosophy

In the late 1990s, the Orchestration-Driven Service-Oriented Architecture emerged as enterprises were rapidly expanding, necessitating sophisticated IT solutions. During this era, companies faced challenges related to limited and expensive computing resources, prompting the adoption of distributed architectures for their scalability benefits. The prevailing constraints were driven by factors such as the cost of operating systems and complex licensing schemes for commercial database servers.

As a result, architects were compelled to maximize reuse. The dominant philosophy underlying this architecture was centered on achieving extensive reuse in all forms, with far-reaching consequences.

Topology

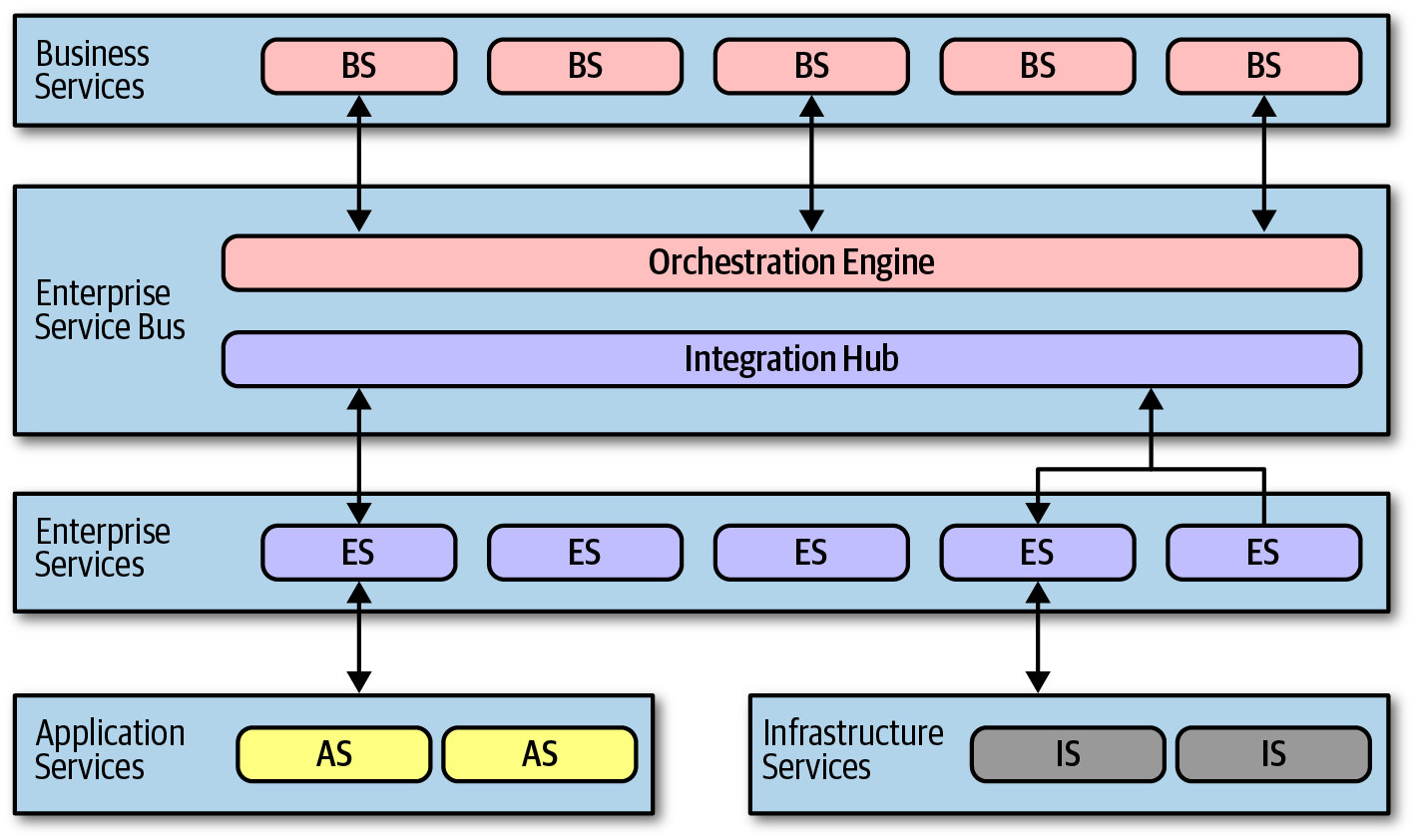

The topology varied among implementations, but the overarching concept involved establishing a taxonomy of services within the architecture, with each layer assigned specific responsibilities.

This style of architecture is inherently distributed, and the precise delineation of boundaries varied depending on the organization's specific requirements and structure.

Example

Topology of orchestration-driven service-oriented architecture from Fundamentals of Software Architecture.

Taxonomy

The services played a crucial role in this architecture centered around enterprise-level reuse. Many large companies were annoyed at how much they had to continue to rewrite software. The various layers in this taxonomy were designed to support this objective.

Business Servicess

Situated at the top of the architecture, business services served as the entry point and encapsulated domain-specific behavior. Examples like ExecuteTrade or PlaceOrder represented essential business activities. These service definitions, often crafted by business users, contained input, output, and schema information but no actual code.

Enterprise Services

Found beneath business services, enterprise services housed fine-grained, shared implementations. Development teams focused on creating atomic behavior around specific business domains, such as CreateCustomer or CalculateQuote. These services acted as the foundational building blocks for the broader business services, connected through an orchestration engine. The goal was to foster reuse by developing finely tuned enterprise services that could be leveraged across various business workflows.

However, the dynamic nature of the business landscape posed challenges to achieving complete stability. Markets, technological advancements, and other factors complicated efforts to establish long-term stability in the software world.

Application Services

Recognizing that not all services required the same level of granularity or reuse, application services were introduced. These were one-off, single-implementation services tailored to specific application needs. For instance, an application might need a geo-location service without the organization investing in making it reusable. Application services were typically owned by a single application team, addressing specific requirements without the expectation of broader reuse.

Infrastructure Services

Handling operational concerns like monitoring, logging, authentication, and authorization, infrastructure services constituted the bottom layer. These services provided concrete implementations and were owned by a shared infrastructure team working closely with operations to ensure the smooth functioning of the overall system.

Orchestration Engine

At the heart of the Orchestration-Driven Service-Oriented Architecture lies the orchestration engine. This pivotal component intricately threads together the implementations of business services through orchestration, encompassing features such as transactional coordination and message transformation. In contrast to microservices architectures, where each service might maintain its database, this architecture typically relies on a single relational database or a few databases. As a result, transactional behavior is declaratively managed within the orchestration engine rather than in individual databases.

The orchestration engine plays a pivotal role in defining the relationships between business and enterprise services, determining their alignment, and establishing transaction boundaries. It also operates as an integration hub, facilitating the seamless integration of custom code with packaged and legacy software systems.

Being the central element of the architecture, the team of integration architects responsible for the orchestration engine tends to emerge as a potent political force within the organization, often evolving into a bureaucratic bottleneck, in line with Conway's law predictions.

While the notion of off-loading transaction behavior to an orchestration tool seemed promising, practical implementation proved to be challenging. Determining the optimal granularity of transactions became increasingly intricate. While constructing a few services encapsulated in a distributed transaction is feasible, the architecture's complexity heightens as developers grapple with defining appropriate transaction boundaries between services.

Message Flow

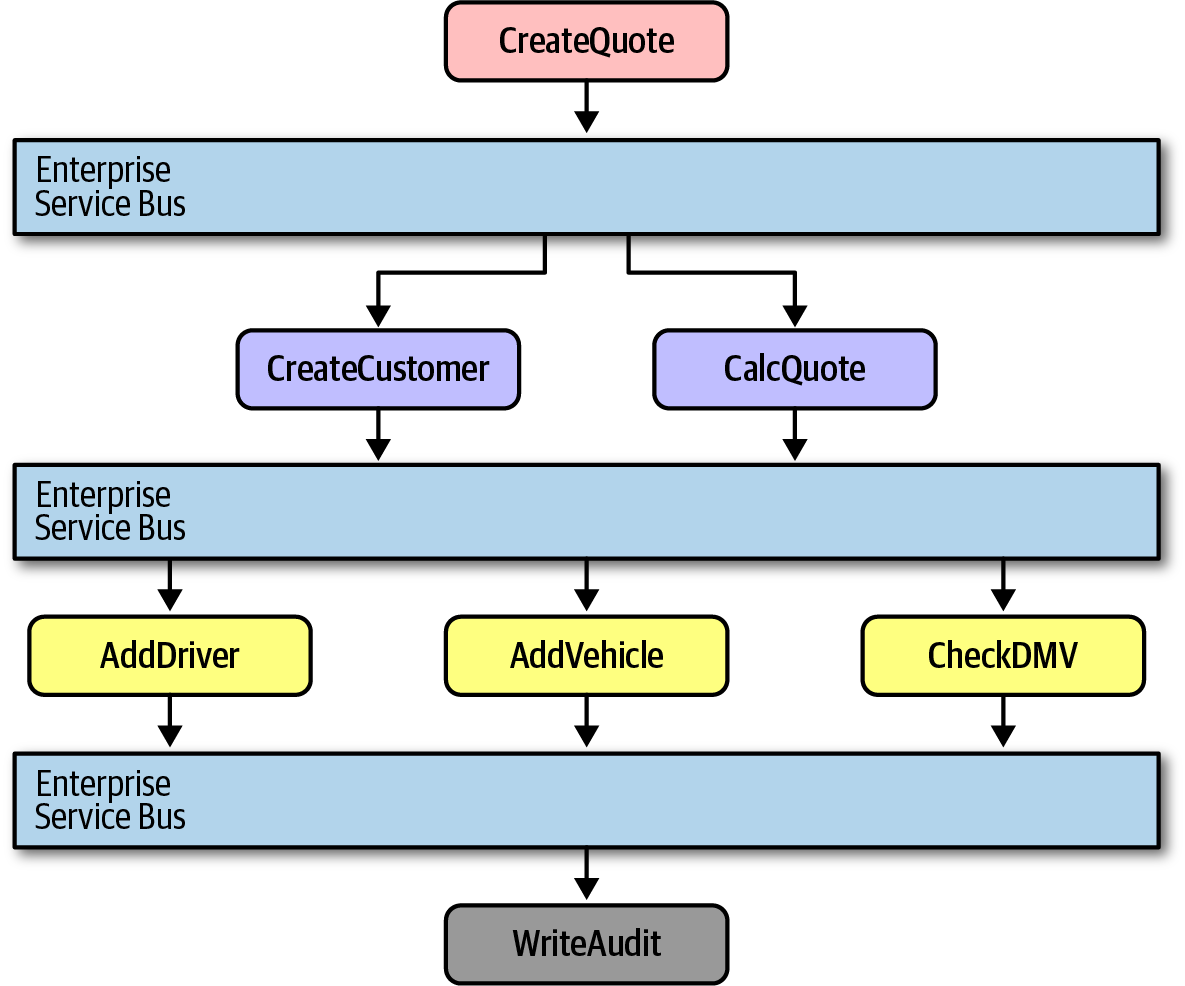

In this architecture, all requests traverse the orchestration engine, serving as the locus of logic. Consequently, the message flow is directed through the engine even for internal calls.

Example

The CreateQuote business-level service initiates a call to the service bus, defining the workflow involving calls to CreateCustomer and CalculateQuote. Each of these, in turn, encompasses calls to application services. The service bus acts as the intermediary for all calls, functioning both as an integration hub and an orchestration engine.

Message flow with service-oriented architecture from Fundamentals of Software Architecture.

Reuse and Coupling Problem

A central objective of this architecture is achieving reuse at the service level, aiming to gradually construct business behavior for incremental reuse over time. Architects were encouraged to actively seek opportunities for reuse in this architecture. However, the realization of negative trade-offs unfolded slowly. Building a system primarily around reuse resulted in significant coupling between components—a consequence of consolidating behavior into a single location. The impracticality of designing an architecture overly focused on technical partitioning became a stark revelation, despite its alignment with separation and reuse philosophies.

Domain concepts, such as CatalogCheckout, suffered from being thinly spread across the architecture, leading to a practical nightmare. Developers found themselves engaged in tasks like "add a new address line to CatalogCheckout," which, in a service-oriented architecture, could involve numerous services across various tiers and changes to a single database schema. If the existing enterprise services lacked the correct transactional granularity, developers faced the dilemma of either altering their design or constructing a new, nearly identical service, undermining the concept of reuse.

Example

Consider a scenario with distinct divisions within an insurance company:

- Auto and Homeowners Insurance Division

- Life Insurance Division

- Commercial Insurance Division

- Disability Insurance Division

- Casualty Insurance Division

- Trave Insurance Division

An architect identifies that each division involves a concept of Customer. The service-oriented architecture strategy suggests extracting customer elements into a reusable service and letting the original services reference the canonical Customer service. However, any change to the Customer service has a ripple effect on all other services, introducing risk to the change process. Consequently, architects grappled with making incremental changes, leading to significant ripple effects, necessitating coordinated deployments, holistic testing, and other impediments to engineering efficiency.

To support a unified Customer service, it must encompass all details known about customers. For instance, auto insurance may require driver's license details, which pertain to the person rather than the vehicle. Consequently, the Customer service would need to include details about driver's licenses that the disability insurance division finds irrelevant. This challenge exemplifies the intricate balance between achieving reuse and managing coupling within the architecture.