Microkernel Architecture Style

The concept of the microkernel architecture, often termed the plug-in architecture, originated many years ago and continues to be a prominent feature in modern software design. This style particularly suits product-based applications, which are typically distributed as a single, comprehensive deployment, installed at the customer's location as a third-party product. Its utility isn't limited to products, as it also finds extensive use in custom-built business applications.

Topology

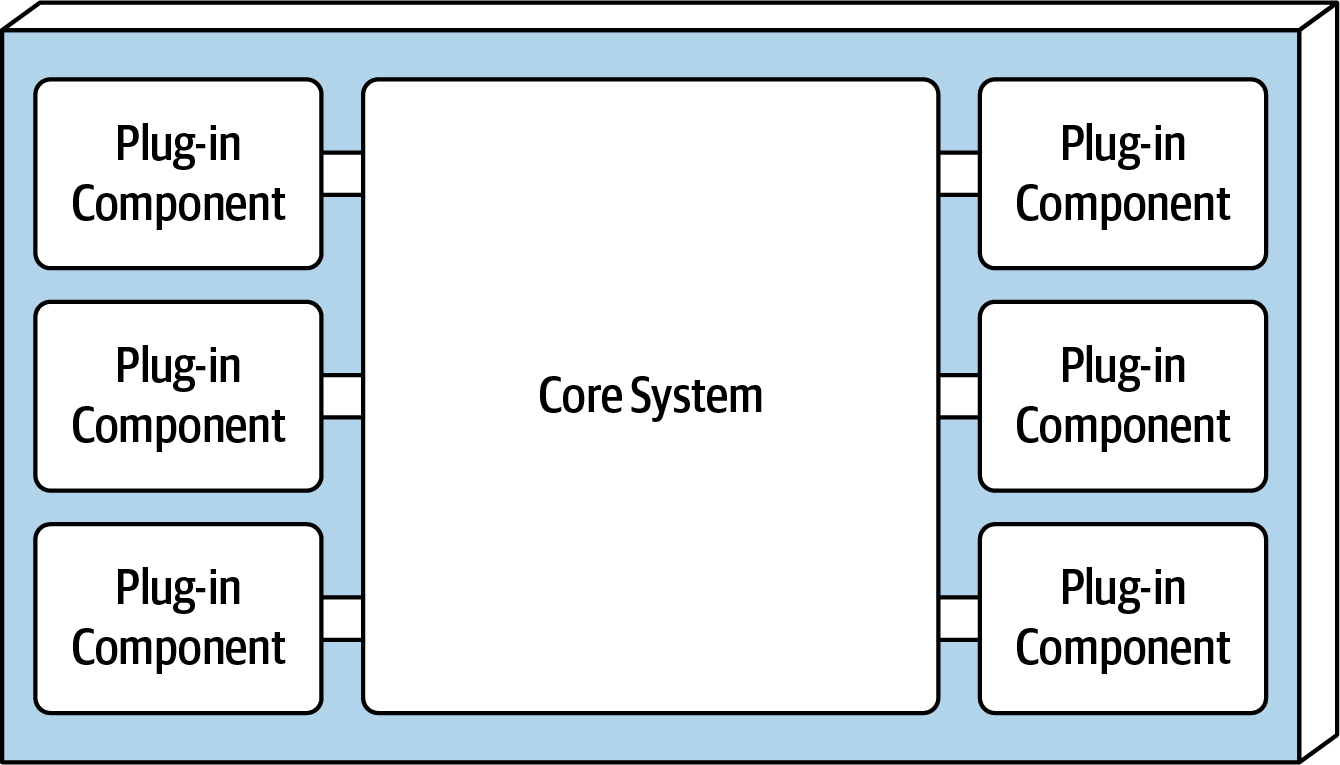

Microkernel architecture is a basic two-components monolithic structure. It consists of a core system and plug-in components. This setup divides the application logic between the autonomous plug-ins and the fundamental core system, allowing for flexibility, customization, and segregation of application features and specific processing logic.

Basic components of the microkernel architecture style from Fundamentals of Software Architecture.

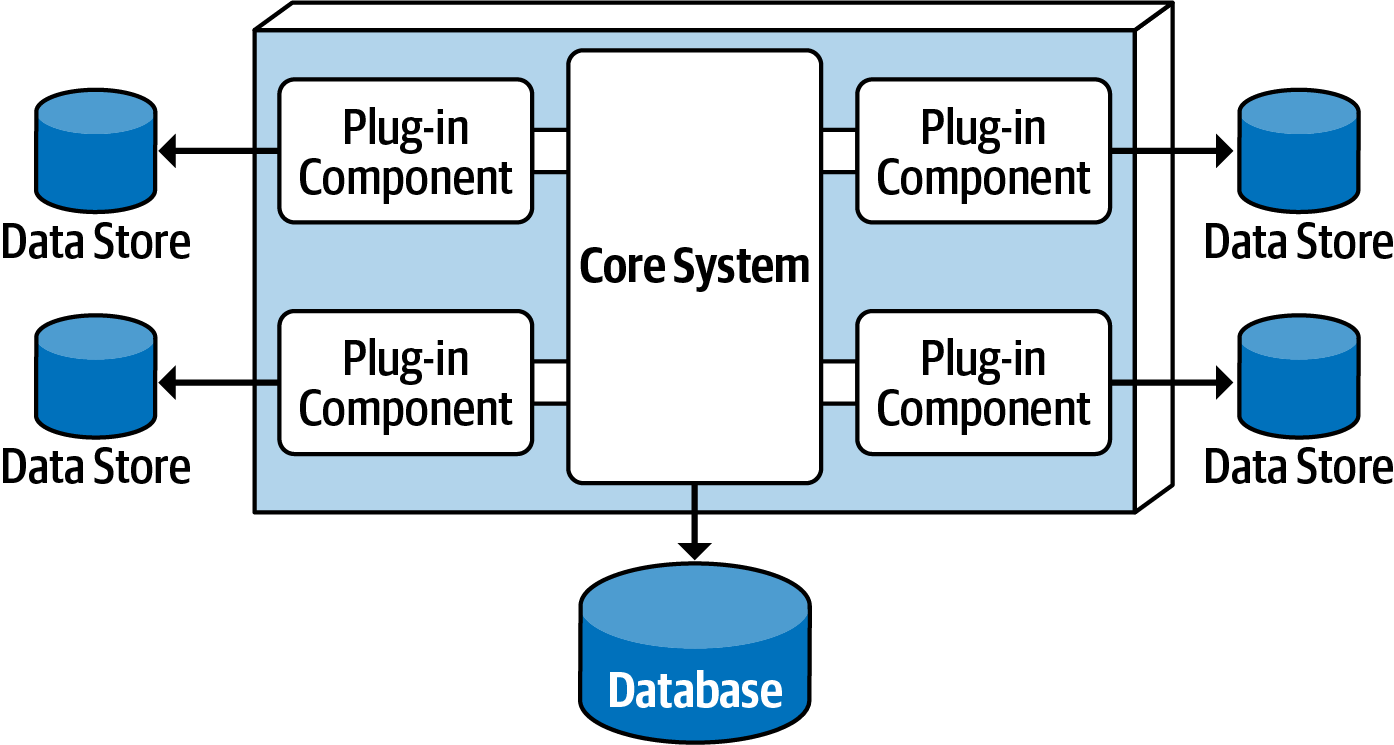

The core system assumes the responsibility of supplying necessary data to each plug-in. Decoupling is the main rationale behind this strategy. Any modifications to the database should only affect the core system, not the plug-in components. However, plug-ins can maintain their own distinct data stores accessible solely to their respective plug-ins.

Plug-in components can own their own data store from Fundamentals of Software Architecture.

Core System

The core system is the essential functionality needed to operate the system. For instance, an IDE it's the basic text editor enabling actions like opening, editing, and saving files. It's only when plug-ins are added that it becomes a fully functional product.

Another definition of the core system is the straightforward path through the application, without custom processing. Transferring complex functions to plug-ins simplifies the core system, making it more extensible, maintainable, and testable.

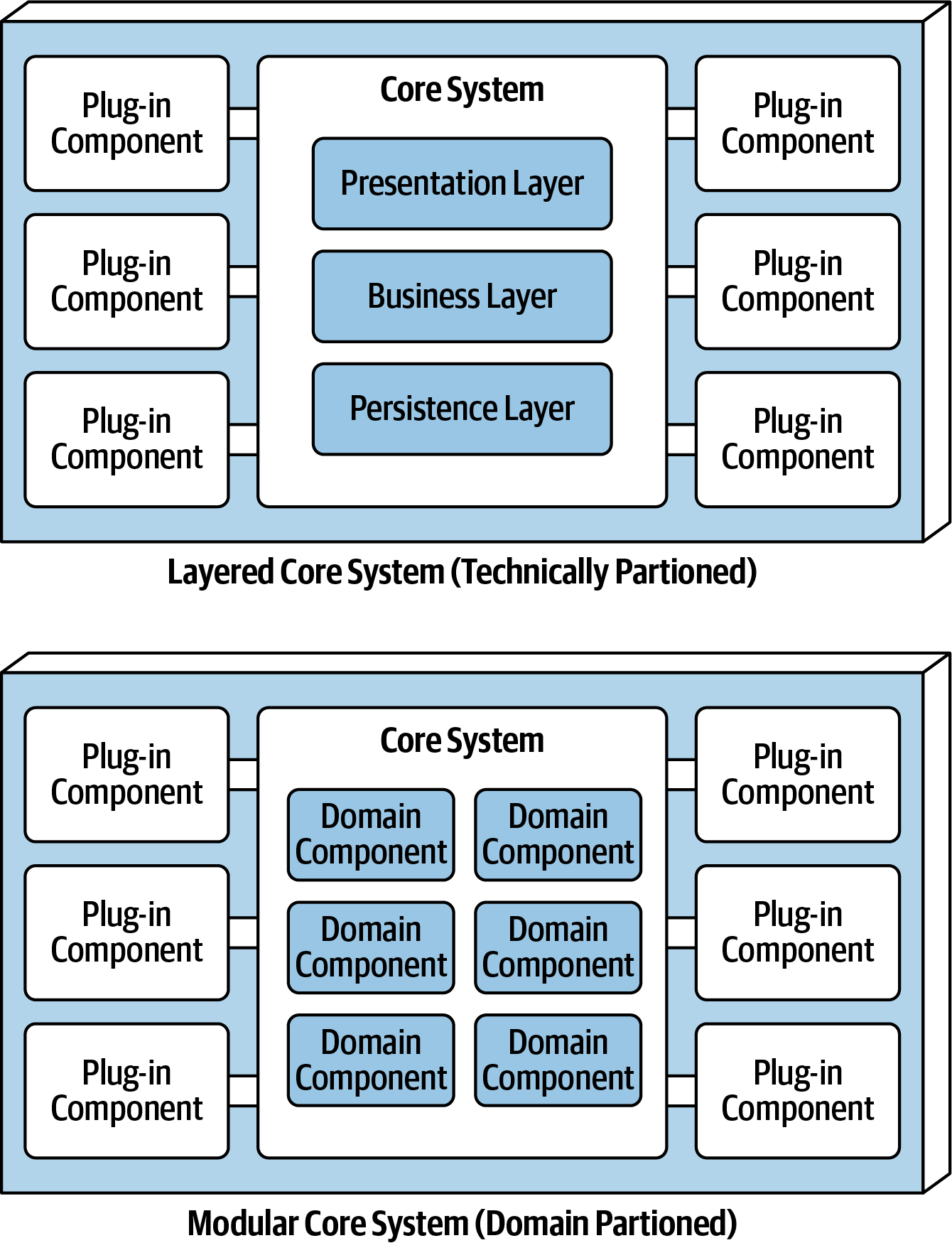

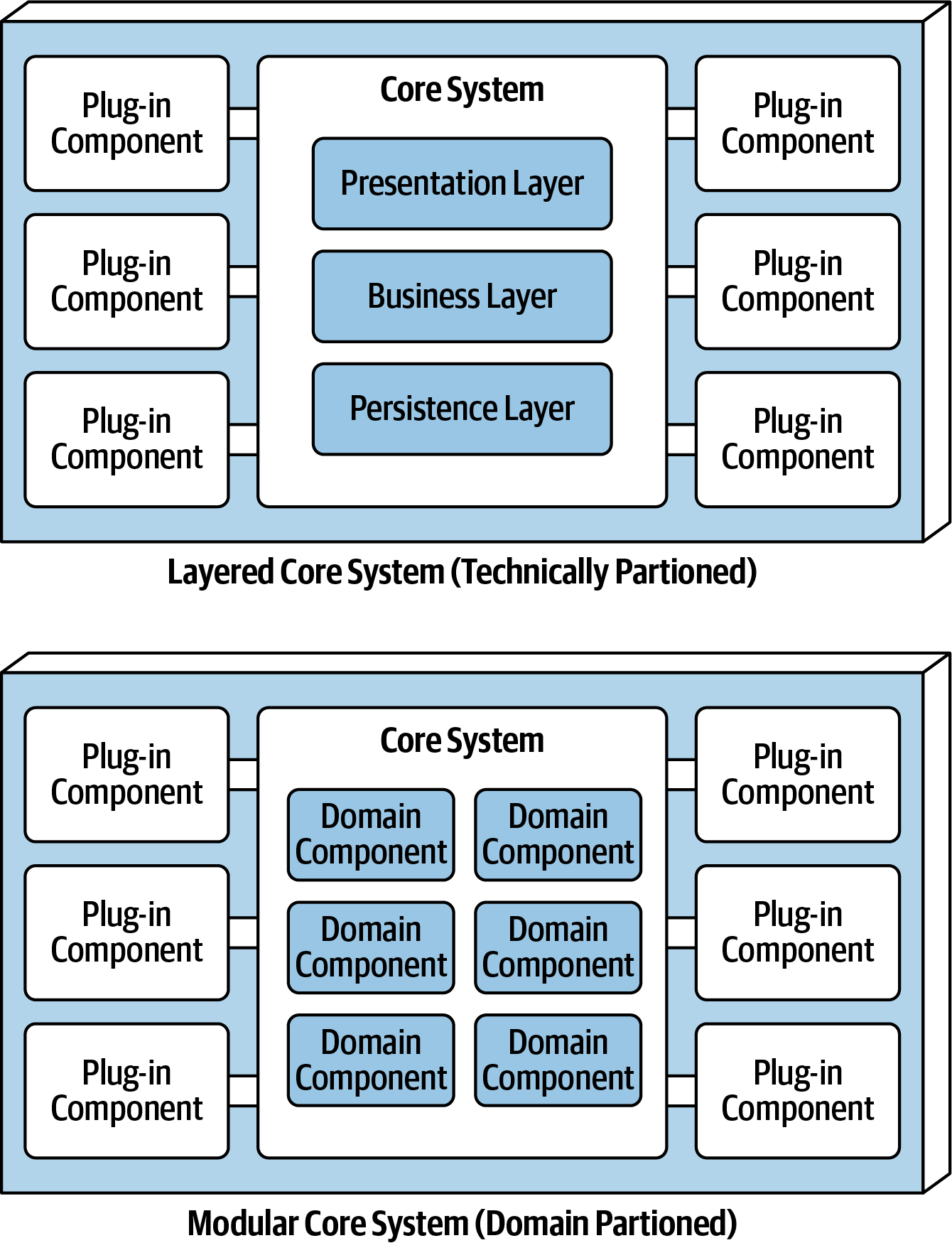

Depending on the application's scale, the core system can be structured as a layered architecture or a modular monolith. Additionally, it can be split into separately deployed domain services, each containing domain-specific plug-in components.

Example

Variations of the microkernel architecture core system from Fundamentals of Software Architecture.

User interface variants from Fundamentals of Software Architecture.

Plug-In Components

Plug-in components are self-contained units housing specific functionalities, additional features, and customized code designed to amplify or extend the core system. They also serve to isolate volatile code, enhancing the application's maintainability and testability. The goal is to ensure plug-in components remain independent without interdependencies.

These plug-in components can be either compile-based or runtime-based. Runtime plug-ins can be added or removed without redeploying the core system or other plug-ins. In contrast, compile-based plug-ins are more straightforward to manage but necessitate redeployment of the entire monolithic application when modified, added, or removed.

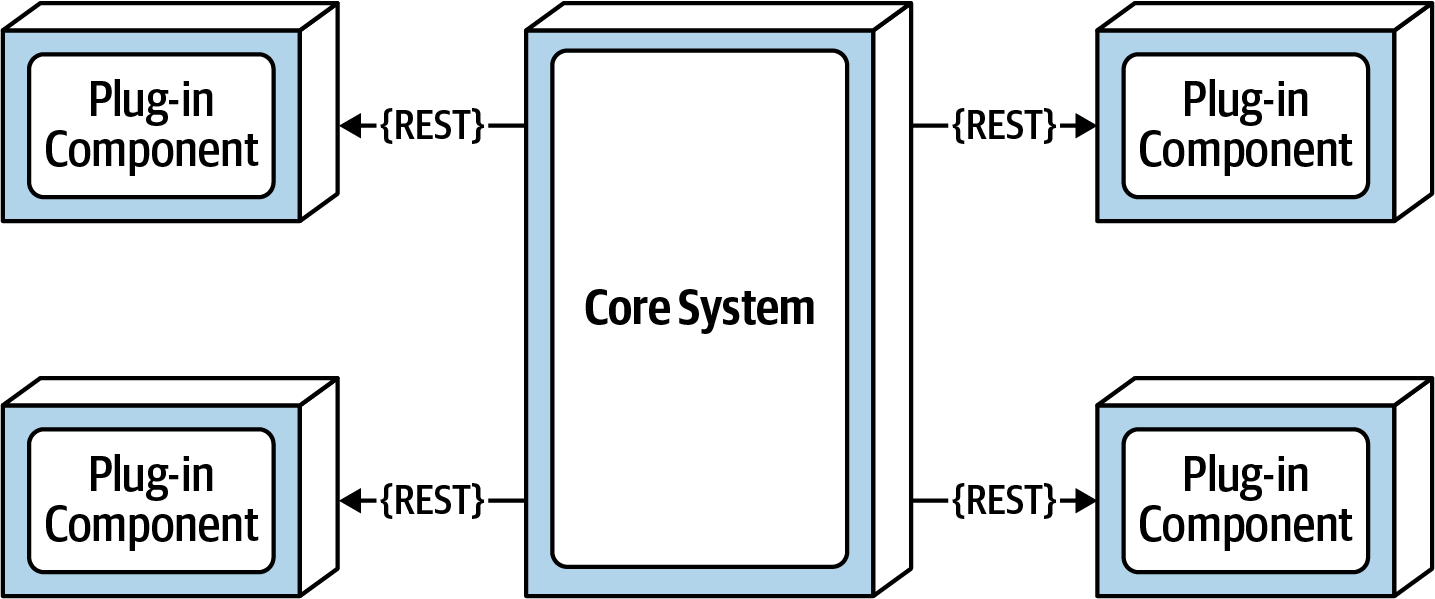

Communication between the plug-in components and the core system typically occurs through point-to-point connections. This connection, often represented as a pipe, is generally a method invocation or function call to the entry-point class of the plug-in component. While plug-in components primarily engage in point-to-point communication with the core system, there are alternatives such as using REST or messaging to invoke plug-in functionality.

In this scenario, each plug-in functions as a standalone service, or even a microservice implemented within a container. Although this approach may seem conducive to scalability, it's important to note that this setup remains a single architecture quantum due to the monolithic core system. Consequently, every request must first pass through the core system to access the plug-in service.

Trade-Offs

Enabling remote plug-in access transforms the microkernel architecture into a distributed one, which can pose challenges for implementing and deploying most third-party on-prem products. Additionally, it introduces increased complexity, higher costs, and complicates the overall deployment structure.

Deciding whether to establish communication to plug-in components from the core system as point-to-point or remote should be based on specific requirements, necessitating a thorough analysis of the trade-offs between the benefits and drawbacks of each approach.

Registry Plug-In Components

For effective communication with plug-in modules, the core system requires knowledge of their availability and access methods. One common approach is the utilization of a plug-in registry. This registry holds comprehensive information about each plug-in module, including its name, data contract, and details about the remote access protocol if applicable.

For instance, a tax software plug-in designed to identify high-risk audit items may feature registry entries containing the service name (AuditChecker), data contract specifications (input and output data), and the contract format (XML).

The registry can be as simple as an internal map structure owned by the core system, containing a key and a reference to the plug-in component. Alternatively, it can manifest as a sophisticated registry and discovery tool, integrated within the core system or externally deployed.

Contracts

Contracts between plug-in components and the core system generally follow standard conventions within a domain of plug-in components. These contracts encompass behavior, input data, and output data returned from the plug-in component. Situations involving third-party plug-in development often involve custom contracts, where the plug-in's contract is beyond your control. In such cases, it is customary to establish an adapter between the plug-in contract and your standard contract. This setup ensures that the core system does not require specialized code for each plug-in.

Plug-in contracts can be implemented using various formats, such as XML, JSON, or object transmission between the plug-in and the core system.

Example

Examples and Use Cases

Numerous software development and release tools are built using the microkernel architecture, including:

- Integrated Development Environments (IDEs) like Eclipse and Visual Code.

- Jira;

- Web browsers like Chrome and Firefox.

This architecture also finds application in extensive business systems. For instance, consider the case of an insurance company handling insurance claims processing.

Managing insurance claims involves intricate processes, with varying regulations across different jurisdictions. Many insurance claim applications rely on complex rules engines to manage this complexity. However, these rules engines can become intricate and challenging to maintain, often requiring extensive resources for even simple rule changes. Implementing the microkernel architecture can effectively address these challenges.

In this setup, the rules for each jurisdiction are stored in separate, standalone plug-in components. These components can either be implemented as source code or specific instances of a rules engine accessible to the plug-in. This allows for the seamless addition, removal, or modification of rules specific to a jurisdiction without affecting other parts of the system. Moreover, it enables the system to add or remove new jurisdictions without causing disruptions elsewhere. In this context, the core system primarily manages the standard processes for filing and processing claims, a component that undergoes infrequent changes.