Event-Driven Architecture Style

The event-driven architecture style is a well-liked method for building applications that need to be both highly scalable and high-performing. It's quite flexible and can be used for both small and large applications, making it a popular choice across the board. This style involves components that process events independently, without being tightly connected. It can be its own architecture style or be part of other styles, like event-driven microservices architecture.

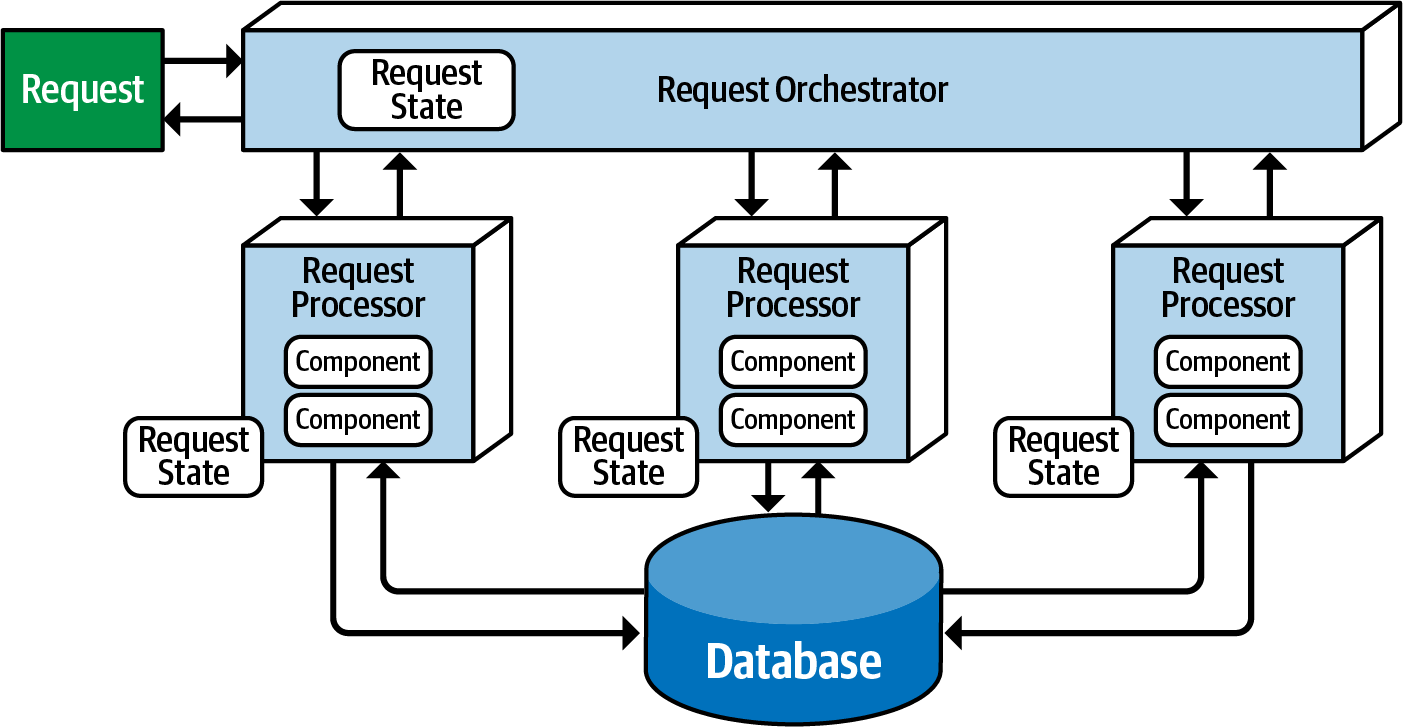

In many applications, there's a request-based approach, where a central system manages and directs various requests to the right places. This can be a user interface, an API layer, or an enterprise service bus. These places handle the requests, dealing with tasks like retrieving or updating data in a database.

Request-based model from Fundamentals of Software Architecture.

Request-Based Example

For instance, when a customer requests their order history for the past six months, it involves retrieving data within a specific context, making it a data-driven, deterministic request. This aligns with the request-based model.

An event-based model responds to specific situations, triggering actions based on those events.

Event-Based Model Example

For example, in an online auction, submitting a bid isn't a direct request to the system but an event that occurs after the current asking price is announced. The system must react to this event by comparing the bid to others received simultaneously, determining the current highest bidder.

Topology

Two main topologies are prevalent in event-driven architecture: the mediator topology and the broker topology. Understanding the distinct characteristics and implementation strategies of these topologies is crucial to determining the most suitable choice for a given situation.

The Mediator Topology

The mediator topology is commonly applied when you need to manage the workflow of an event process.

The Broker Topology

The broker topology is favored when you need swift responsiveness and dynamic control over event processing.

Broker Topology

The broker topology in event-driven architecture differs from the mediator topology by not having a central event mediator. Instead, the message flow is spread across the event processor components in a chain-like broadcasting style through a lightweight message broker. This topology is beneficial for relatively straightforward event processing flows where central event orchestration and coordination are unnecessary.

There are four main parts in the broker topology: an initiating event, the event broker, an event processor, and a processing event.

Initiating Event

This is the starting point of the entire event flow.

Event Broker

The initiating event is sent to an event channel in the event broker for processing.

Event Processor

Since there is no mediator component, a single event processor receives the initiating event from the event broker and begins the processing of that event. The event processor executes a specific task related to the event and asynchronously broadcasts its actions to the entire system, creating a processing event.

Processing Event

This processing event is then sent to the event broker for further processing, if necessary. Other event processors, upon listening to the processing event, react to it by performing actions and then advertise, through a new processing event, what they did. This process continues until no one is interested in the actions of a final event processor.

In the broker topology, it is considered good practice for each event processor to advertise its actions to the entire system, even if other event processors may not be concerned. This practice ensures architectural extensibility in case additional functionality is required for processing that event.

Email Notifying

Suppose an email needs to be generated and sent to a customer to inform them about a specific action.

1. The Notification event processor generates and dispatches the email.

1. It then advertises this action to the entire system by creating a new processing event, sending it to a topic.

1. However, since no other event processors are tuned in to events on that topic, the message simply fades away without any further impact.

Here's a notable illustration of architectural extensibility. Although it might appear inefficient to send messages that go unnoticed, it holds significant value. Consider a scenario where a new requirement emerges to analyze emails sent to customers. With the current system:

- A new

event processor for analyzing emails can seamlessly be introducedwith minimal effort. - The email information is readily accessible via the email topic, allowing the new analyzer to function without the need for additional infrastructure or changes to other event processors.

More Deep Example

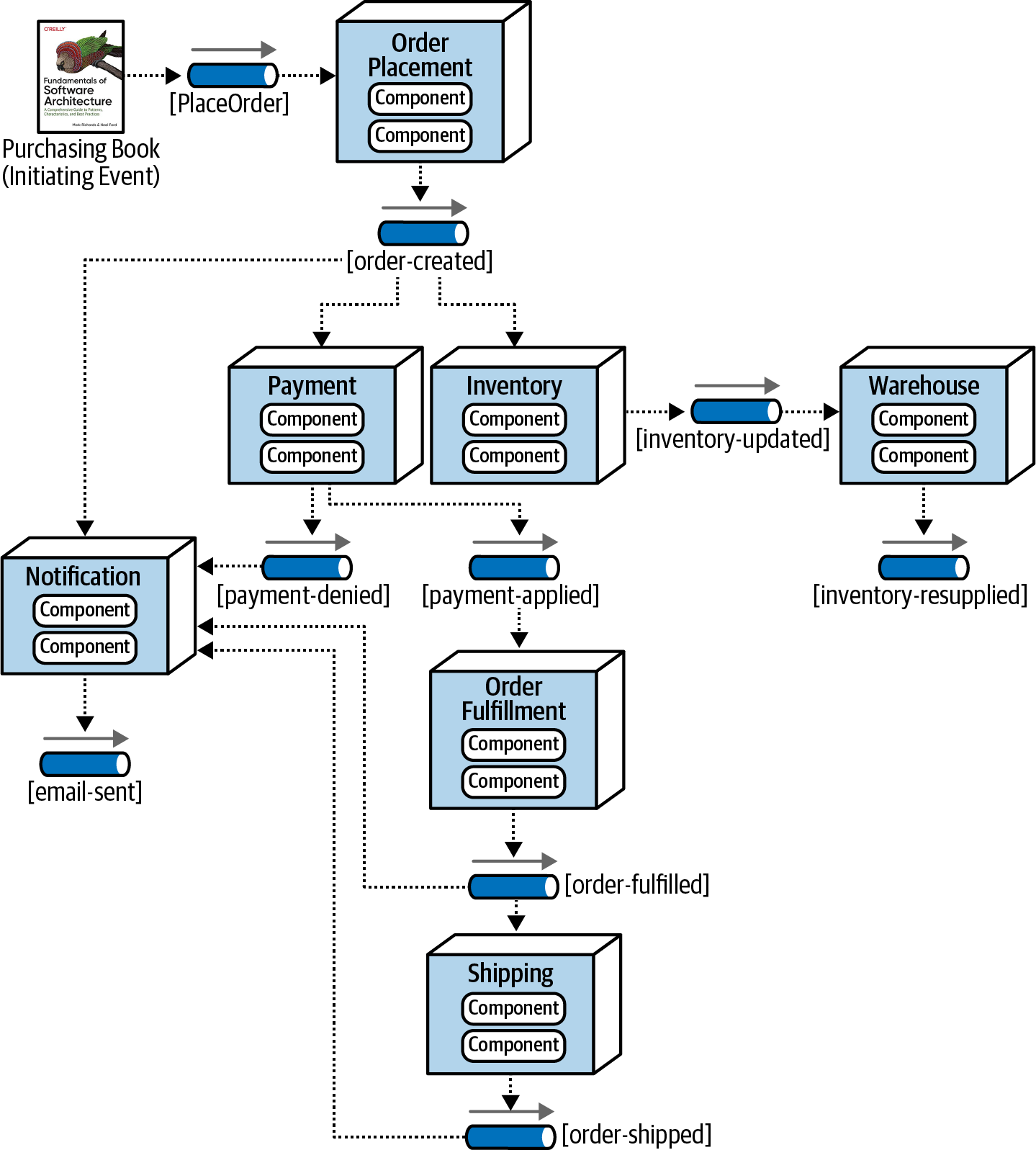

Example of the broker topology Fundamentals of Software Architecture.

- The

initial eventis "Purchasing Book." - The

event brokeris represented by the[PlaceOrder]pipe. Event processorsare depicted as boxes, likeOrderPlacement,Payment,Notification, etc.Processing eventsare illustrated by pipes with arrows and names in lowercase, like[order-created],[inventory-updates],[payment-denied], etc.

It's evident that all event processors are highly decoupled and operate independently. Once an event processor hands off the event, it ends involvement in the processing of that specific event, remaining available to react to other initiating or processing events. Moreover, each event processor can scale independently to handle varying load conditions or backups in the event processing.

While the broker topology offers benefits in terms of performance, responsiveness, and scalability, there are drawbacks. Firstly, there is no control over the overall workflow associated with the initiating event. The system lacks awareness of when the business transaction of placing an order is truly complete. Error handling poses a significant challenge in the broker topology. Without a mediator monitoring or controlling the business transaction, a failure goes unnoticed, leading to a stuck business process that requires automated or manual intervention to resolve.

Recovering from a business transaction (recoverability) is not supported in the broker topology. As other actions are asynchronously taken during the initial processing of the initiating event, resubmitting the initiating event becomes impractical. No component in the broker topology is aware of or owns the state of the original business request, leaving no one responsible for restarting the business transaction and knowing its progress.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

Highly decoupled event processors |

Workflow control |

High scalability |

Error handling |

High responsiveness |

Recoverability |

High performance |

Restart capabilities |

High fault tolerance |

Data inconsistency |

Mediator Topology

In the mediator topology, a central figure is the event mediator, overseeing and orchestrating the workflow for initiating events that necessitate the coordination of multiple event processors. The key components of the mediator topology include an initiating event, an event queue, an event mediator, event channels, and event processors.

Initiating Event

- This is the event that initiates the entire eventing process.

The initiating event is directed to an initiating event queue, which is then received by the event mediator.

Event Mediator

- Manages the workflow, generating corresponding processing events dispatched to dedicated event channels (usually queues) in a point-to-point messaging style.

Event Processors

- Attend to their tasks by

monitoring dedicated event channels, executing event-specific processes, and typically communicating back to the mediator upon task completion. - Unlike the broadcast approach of the broker topology,

event processors in the mediator setup operate discreetly without announcing their actions to the entire system.

Practical implementations often deploy multiple mediators, each linked to a specific domain or category of events. This strategic approach mitigates the risk of a single point of failure, enhancing overall system resilience and performance.

The mediator component, distinctive from the broker topology, boasts both knowledge and command over the workflow. This capability empowers the mediator to uphold event states and proficiently manage aspects like error handling, recoverability, and restart functionalities.

A fundamental disparity surfaces between the processing events in broker and mediator topologies concerning their meaning and utilization. In the broker paradigm, processing events serve as published occurrences in the system (e.g., order-created, payment-applied, email-sent), triggering subsequent actions and reactions among event processors. Using the mediator topology, processing events (e.g., place-order, send-email, fulfill-order) are akin to commands, dictating necessary actions rather than merely reporting past events. Notably, in the mediator domain, a command necessitates processing, while an event in the broker setup can be disregarded.

Challenges within the Mediator Domain

Although event processors can scale comparably to the broker setup, the mediator's scaling introduces occasional bottlenecks in the overarching event processing flow. Additionally, event processors in the mediator setup lack the high level of independence seen in the broker model, impacting overall performance due to the mediator's active role in controlling event processing.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

Workflow control |

More coupling of event processors |

Error handling |

Lower scalability |

Recoverability |

Lower performance |

Restart capabilities |

Lower fault tolerance |

Better data consistency |

Modeling complex workflows |

Asynchronous Capabilities

The event-driven architecture style presents a distinctive feature compared to other architectural approaches by relying entirely on asynchronous communication. This encompasses both fire-and-forget processing, where no response is required, and request/reply processing, where a response is expected from the event consumer. Leveraging asynchronous communication proves to be a potent technique for enhancing overall system responsiveness.

Responsiveness vs Performance

In scenarios where the user doesn't necessitate immediate feedback beyond an acknowledgment or a simple thank-you message, why subject them to unnecessary waiting? Responsiveness focuses on promptly notifying the user that their action has been acknowledged and will undergo processing shortly. Conversely, performance revolves around expediting the end-to-end process.

The challenge in asynchronous behavior arises when the user's action encounters rejection, as there's no direct route to communicate this back to the end user. While a message signaling an issue could be dispatched, in more intricate scenarios, this might not constitute a comprehensive solution. The primary hurdle in asynchronous communications lies in error handling. Although responsiveness sees a significant boost, effectively addressing error conditions adds complexity to the event-driven system.

Error Handling - Workflow Event Pattern

The workflow event pattern within reactive architecture provides a solution to the challenges associated with error handling in an asynchronous workflow. This pattern, inherent to reactive architecture, effectively addresses both resiliency and responsiveness, ensuring that the system remains robust in handling errors without compromising responsiveness.

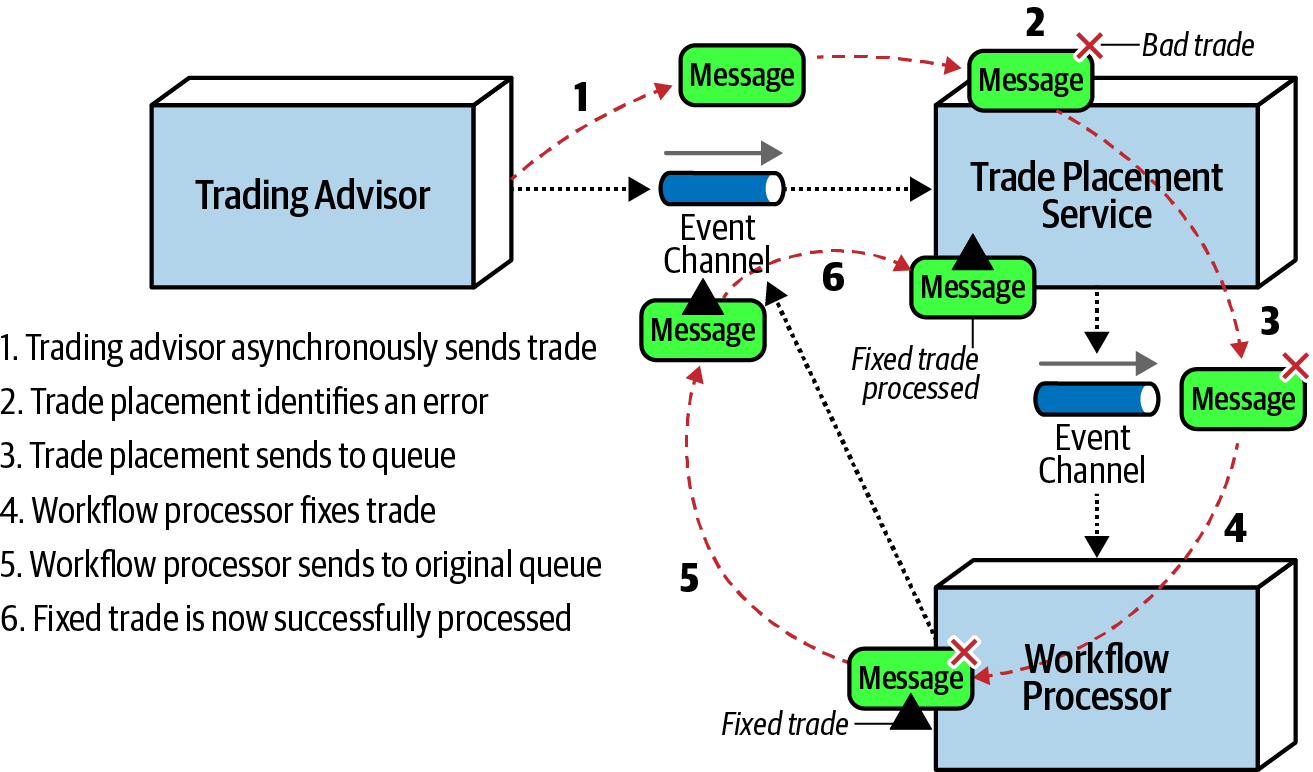

In this approach, the event producer asynchronously transmits data through a message channel to the event consumer. When the event consumer encounters an error in processing, it promptly delegates the error to the workflow processor and proceeds to process the next message in the event queue. This ensures that overall responsiveness is maintained, as errors don't become impediments to processing subsequent messages. If the event consumer were to spend time resolving the error, it would impede not only the responsiveness of the next message but also impact all other messages waiting in the queue for processing.

Upon encountering an error, the workflow processor engages in a diagnostic process to identify issues within the message. This diagnostic phase may involve recognizing static, deterministic errors or deploying machine learning algorithms to detect anomalies in the data. The workflow processor then programmatically applies changes to the original data in an attempt to repair it. The corrected data is subsequently re-entered into the originating queue. From the perspective of the event consumer, this corrected message is treated as new, prompting another processing attempt. In scenarios where the workflow processor cannot definitively pinpoint the issue, the message is redirected to an alternative queue, commonly known as a dashboard.

This dashboard, resembling familiar email applications, usually resides on the desktop of a key individual. Here, the individual reviews the message, introduces manual fixes if needed, and then reissues it to the original queue, often utilizing a "reply-to" message header variable.

A noteworthy consequence of the workflow event pattern is messages encountering errors undergo processing out of their original sequence upon resubmission. Preserving the exact order of messages within a specific context proves to be a complex task. A potential solution to this challenge involves storing the errored messages temporarily in a dedicated queue. Any data processing with the same identification (like ID) would be stored in a temporary queue for later processing (in FIFO order). Once the error is fixed and processed, the service then de-queues the remaining trades for that same identification and processes them in order.

Example

Consider a scenario where a trading advisor, situated in one part of the country, manages trade orders for a prominent trading firm located elsewhere. The advisor efficiently compiles trade orders into a basket and dispatches them asynchronously to the large trading firm for execution through a broker. The contractual format for trade instructions encompasses fields such as: ACCOUNT (String), SIDE (String), SYMBOL (String), and SHARES (Long).

Imagine the large trading firm receives a basket of Apple (AAPL) trade orders from the advisor:

12654A87FR4,BUY,AAPL,1254

87R54E3068U,BUY,AAPL,3122

2WE35HF6DHF,BUY,AAPL,8756 SHARES

6R4NB7609JJ,BUY,AAPL,5433

In a scenario without of error-handling capabilities, an error would surface on the line with SHARES. In this asynchronous context, when an exception occurs, the trade placement service lacks the means for synchronous user intervention. The only recourse might be logging the error condition.

Integrating the workflow event pattern provides a programmatic resolution to such errors. As the large trading firm lacks control over the trading advisor's data, it must autonomously fix the error itself. When the error occurs (2WE35HF6DHF,BUY,AAPL,8756 SHARES), the Trade Placement service promptly delegates the error via asynchronous messaging to the Trade Placement Error service. This delegation includes the error information.

The Trade Placement Error service, operating as the workflow delegate, receives and inspects the exception, identifying it as a "SHARES" issue in the shares field. Subsequently, the Trade Placement Error service removes the term "SHARES" and resubmits the trade for reprocessing, effectively addressing the error within the workflow event pattern.

Error handling with the workflow event pattern from Fundamentals of Software Architecture.

Preventing Data Loss

Mitigating data loss is a critical consideration in the realm of asynchronous communications, particularly within an event-driven architecture. Several points in this system can lead to data loss, meaning messages might accidentally be dropped or fail to reach their intended destination. The good news is that there are basic methods available to prevent data loss in asynchronous messaging situations.

Example

Consider a scenario where Event Processor A sends a message to a queue, subsequently processed by Event Processor B, which inserts the message data into a database. Three potential areas of data loss emerge:

1. Message Fails to Reach the Queue

The message fails to reach the queue from Event Processor A, or if it does, the broker goes down before the next event processor retrieves the message.

Guaranteed Delivery with Persistent Message Queues and Synchronous Send

Leveraging persistent message queues ensures guaranteed delivery. Messages are stored in both memory and a physical data store, facilitating retrieval even if the broker experiences downtime.Synchronous send involves a blocking wait in the message producer until the broker confirms the message's persistence. This combination prevents message loss between the producer and the queue.

2. Event Processor Crashes Before Processing

Event Processor B dequeues the next message but crashes before processing it.

Client Acknowledge Mode for Crash Resilience

- By default, when a message is de-queued, it is immediately removed from the queue (

auto acknowledge mode). - Client acknowledge mode

retains the message in the queue and associates the client ID with it, preventing other consumers from reading the message. - In the

event of a crash, the message remains preserved in the queue, averting message loss in this part of the message flow.

3. Data Error When Saving to the Database

Event Processor B encounters difficulty persisting the message to the database due to a data error.

ACID Transactions and Last Participant Support (LPS) for Database Persistence

- ACID transactions, specifically atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability, are employed via a

database commit, ensuring the data's persistence in the database. - Last participant support (LPS)

acknowledges the completion of processing and message persistence, removing the message from the persisted queue. This guarantees the entire workflow, from the Event Processor A to the database.

Broadcast Capabilities

In event-driven architecture, another distinctive feature is the ability to broadcast events without knowing who will receive the message or what they will do with it, if anything.

Broadcasting represents a significant level of decoupling between event processors. The producer of the broadcast message typically lacks knowledge about which event processors will receive the message and, more crucially, what actions they will take in response. Broadcast capabilities play a vital role in patterns for eventual consistency, complex event processing (CEP), and various other scenarios.

Request-Reply

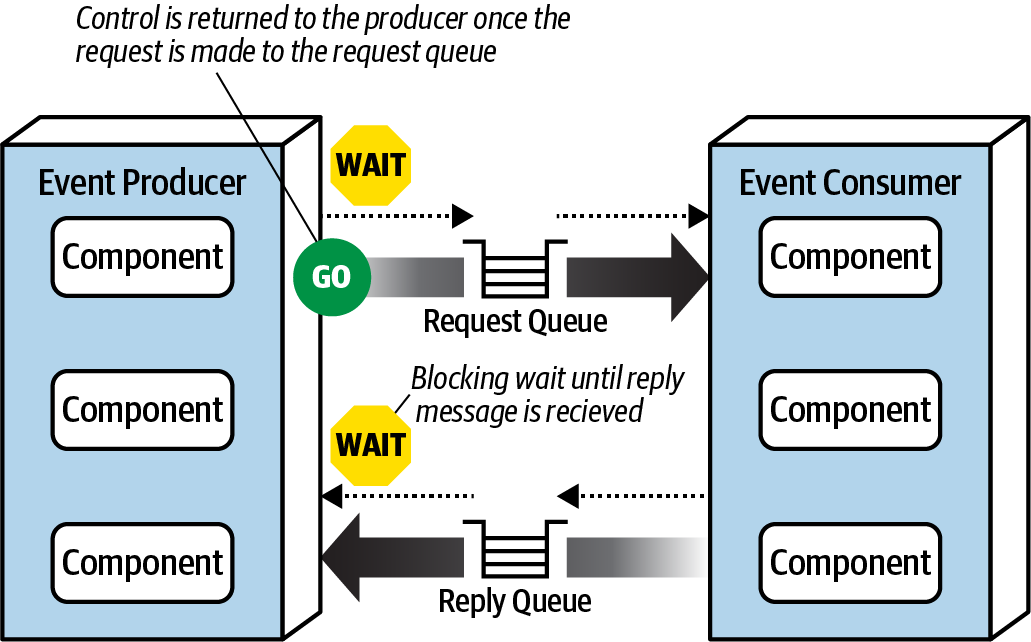

In scenarios where it's essential to receive information, such as an order ID when ordering a book or a confirmation number when booking a flight, synchronous communication between services or event processors becomes necessary.

Within event-driven architecture, synchronous communication is facilitated through request-reply messaging. In request-reply messaging, each event channel comprises two queues:

- a request queue

- a reply queue

Workflow

- The

initial requestfor information is asynchronouslysent to the request queue. - Control is then returned to the

message producerafter sending the request. - The

message producerwaits for the response by blocking on thereply queue. - The

message consumerreceives and processes the message,sending the response to the reply queue. - Finally, the event producer receives the message containing the response data.

Request-reply message processing from Fundamentals of Software Architecture.

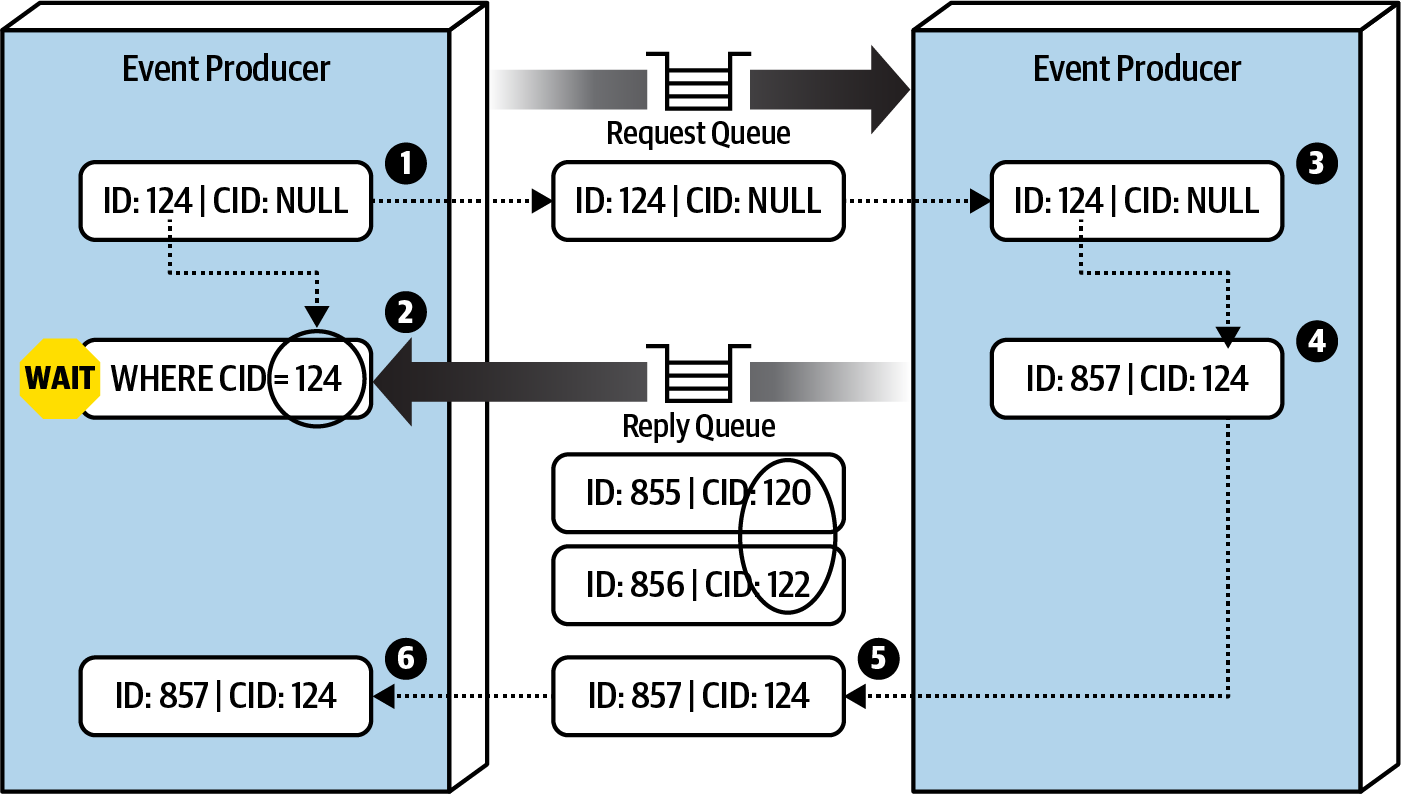

Two primary techniques are commonly used to implement request-reply messaging. The first and most common technique involves utilizing a correlation ID contained in the message header. This correlation ID is a field in the reply message typically set to the message ID of the original request message.

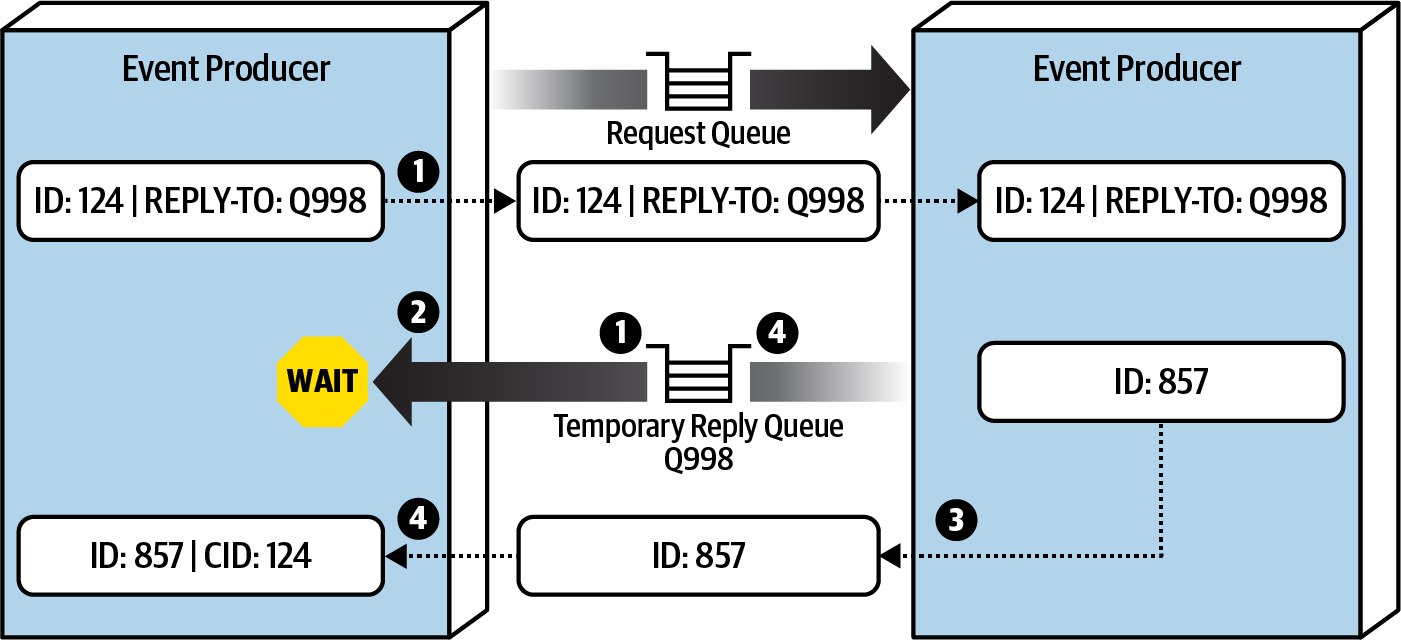

The second technique for implementing request-reply messaging is to use a temporary and exclusive queue for the reply queue. A temporary queue is dedicated to the specific request, created when the request is made, and deleted when the request concludes.

Warning

While the temporary queue technique is simpler, it comes with the drawback of the message broker having to create and immediately delete a temporary queue for each request. In scenarios with high messaging volumes, this can significantly slow down the message broker, impacting overall performance and responsiveness.

Using Correlation ID

- The

event producer sends a message to the request queue and notes the unique message ID(124). Notably, the correlation ID (CID) is null in this case. - The

event producer then waits for a reply on the reply queue, using a message filter.- The

filter looks for messages where the correlation ID in the header matches the original message ID(124).

- The

- The

event consumerreceives and processes the message (ID 124). - The

event consumer generates a reply message, including the response andsetting the correlation ID (CID) in the header to the original message ID(124). - The

event consumer sends the new message (ID 857) to the reply queue. - The

event producer, waiting for a reply,receives the message (ID 857) because the correlation ID (124) matches the message selector from step 2.

Request-reply message processing using a correlation ID from Fundamentals of Software Architecture.

Using Temporary and Exclusive Queue

- The

event producer creates a temporary queue (or one is automatically created, depending on the message broker) and sends a message to the request queue, including the name of the temporary queue in the reply-to header (or another identifier). - The

event producer waits for a reply on the temporary queue. This queue isexclusive to the event producer that initiated the request. - The

event consumerreceives the message, processes the request, and sends a response message to thereply queue named in the reply-to header. - The e

vent producer, waiting on the temporary queue,receives the response message and deletes the temporary queue.

Request-reply message processing using a temporary queue from Fundamentals of Software Architecture.

Choosing Between Request-Based and Event-Based

It is advisable to opt for the request-based model when dealing with well-structured, data-driven requests, such as retrieving customer profile data, where certainty and control over the workflow are crucial. On the other hand, the event-based model is recommended for handling flexible, action-based events that demand high levels of responsiveness and scalability, especially in scenarios involving complex and dynamic user processing.

Trade-offs Table

Advantages over request-based |

Trade-offs |

|---|---|

| Better response to dynamic user content | Only supports eventual consistency |

| Better scalability and elasticity | Less control over processing flow |

| Better agility and change management | Less certainty over outcome of event flow |

| Better adaptability and extensibility | Difficult to test and debug |

| Better responsiveness and performance | |

| Better real-time decision making | |

| Better reaction to situational awareness |

Hybrid Event-Driven Architectures

While many applications use the event-driven architecture as their primary structure, it's quite common to blend it with other styles, forming what's called a hybrid architecture. Examples include combining event-driven architecture with microservices and space-based architecture. You can also create hybrids like an event-driven microkernel or an event-driven pipeline architecture.

Integrating event-driven architecture into any style has advantages—it eliminates bottlenecks, establishes a backpressure point for potential backups in event requests, and enhances user responsiveness beyond what other styles offer. In both microservices and space-based architecture, messaging plays a crucial role as data pumps, facilitating asynchronous data transmission to another processor, which then updates the database. These architectures leverage event-driven principles to scale services in a microservices architecture and processing units in a space-based architecture, especially when using messaging for interservice communication.