Analyzing Architecture Risk

Every architectural design carries inherent risks, whether they involving to availability, scalability, or data integrity. Analyzing these risks constitutes a crucial aspect of the architectural process. Continuous risk analysis empowers architects to identify weaknesses within the design and proactively take corrective measures to mitigate potential issues.

Risk Matrix

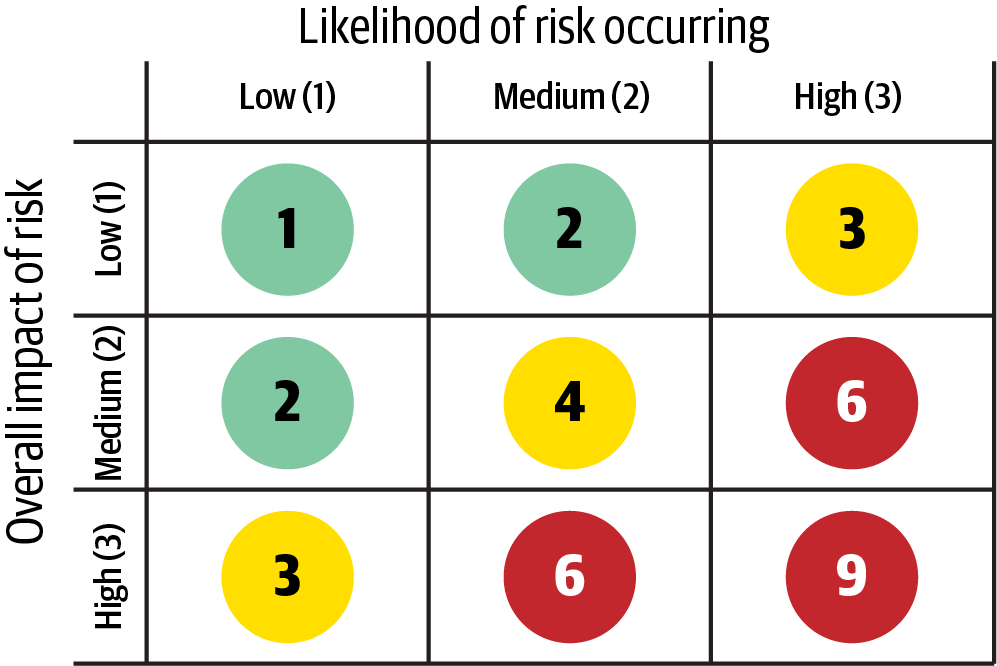

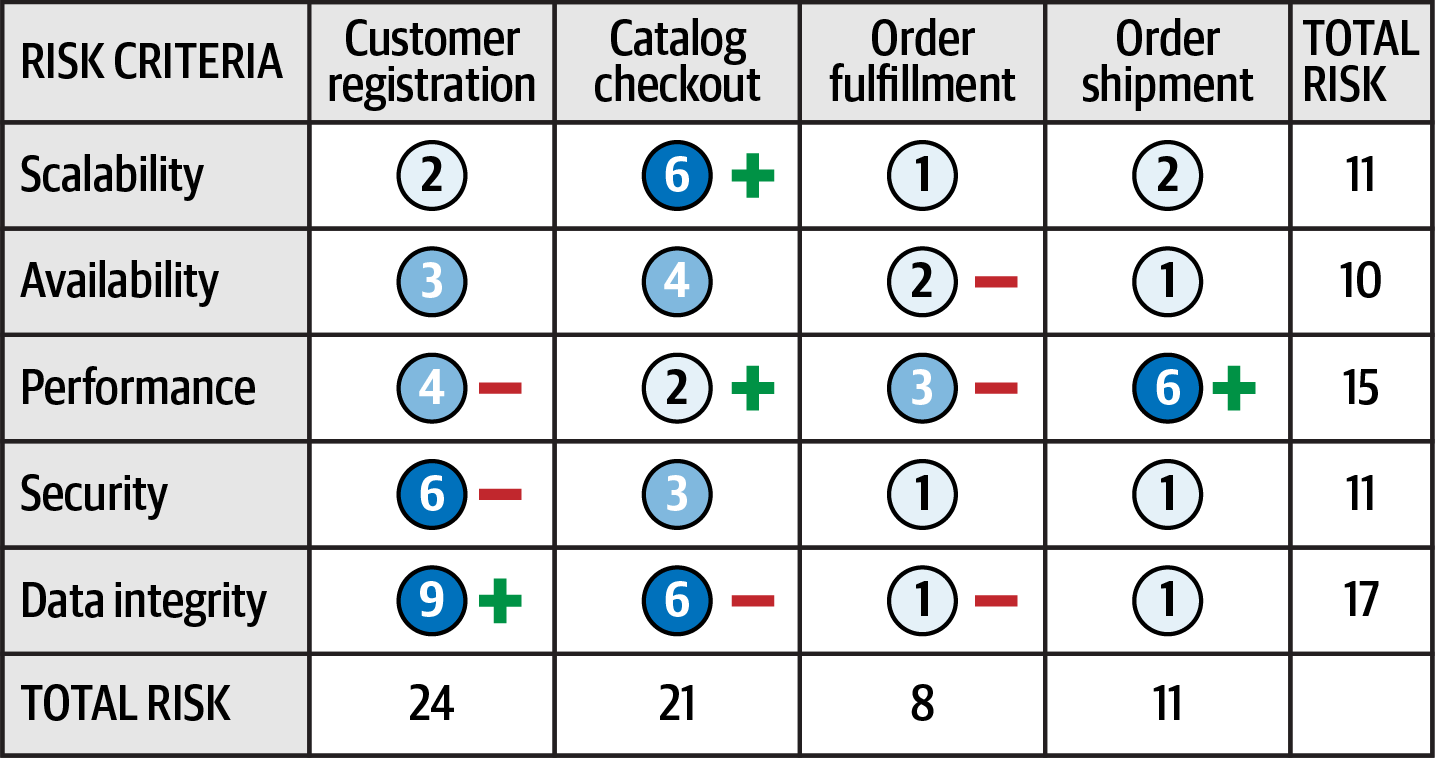

An initial challenge in evaluating architecture risks lies in the subjective classification of risks as low, medium, or high. This subjectiveness can lead to ambiguity regarding the true risk levels in different parts of the architecture. Architects can utilize a risk matrix to inject objectivity into the process and categorize risks associated with specific architectural components.

The architecture risk matrix employs two dimensions to assess risk: the overall impact of risk and the likelihood of its occurrence. Each dimension is assigned a rating of low (1), medium (2), or high (3). These ratings are multiplied within each matrix grid, yielding an objective numerical representation of the risk.

Database Risk

Consider a scenario where there are concerns about the availability of a central database in the application. Initially, assess the impact dimension by evaluating the potential consequences if the database were to go down. An architect may determine this as a high-risk scenario, assigning a rating of 3 (medium), 6 (high), or 9 (high). However, factoring in the second dimension, which evaluates the likelihood of the risk occurring, the architect may realize that the database is hosted on highly available servers in a clustered configuration, minimizing the chances of unavailability. Consequently, the intersection between high impact and low likelihood results in an overall risk rating of 3 (medium risk).

Risk Assessments

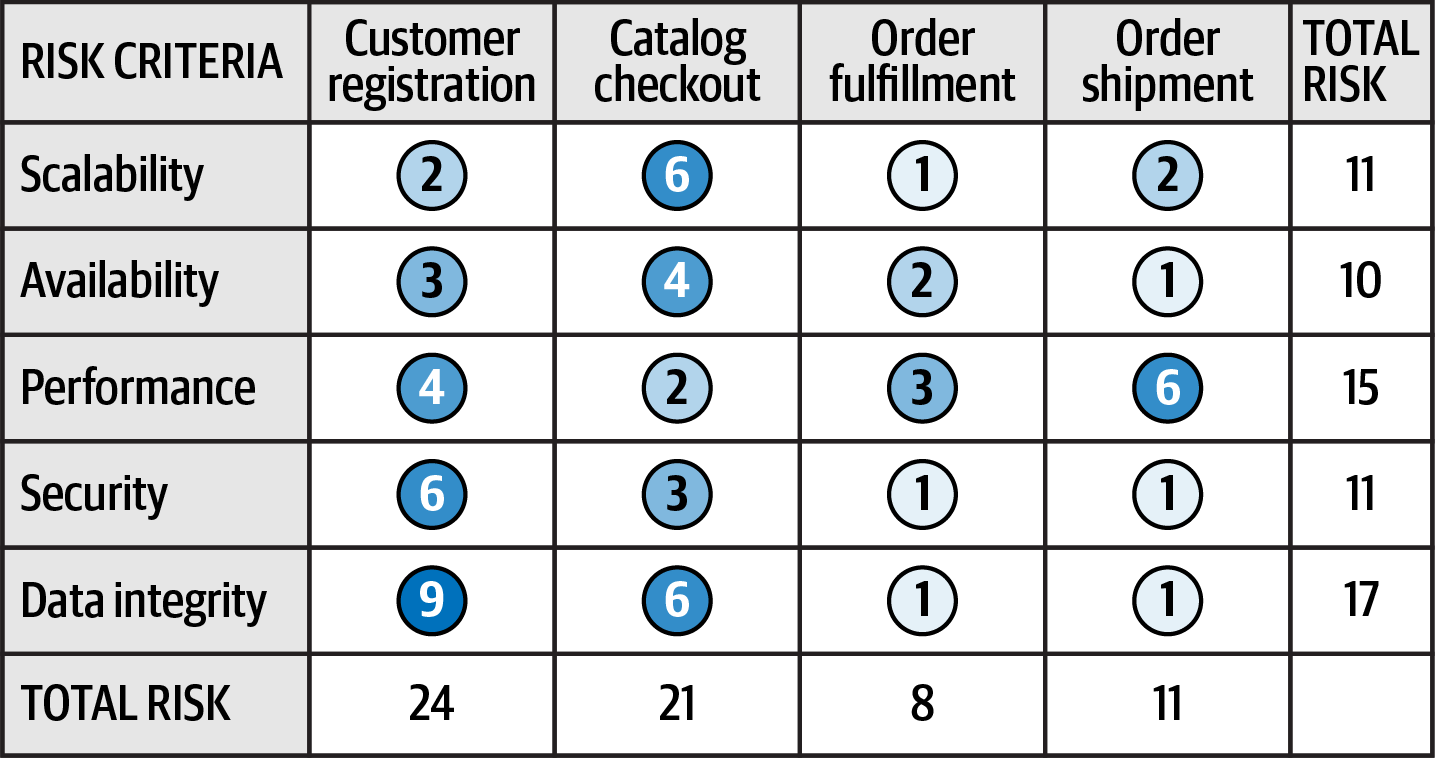

A risk assessment serves as a concise overview of an architecture's overall risk, contextualized against specific assessment criteria. Leveraging the risk matrix becomes pivotal in constructing meaningful risk assessments.

While the format of risk assessments can vary, they generally encapsulate the risk, as qualified by the risk matrix, associated with particular assessment criteria within the application's services or domain areas. The typical report format employs use (1-2) denoting low risk, (3-4) indicating medium risk, and (6-9) signifying high risk. Often color-coded as green (low), yellow (medium), and red (high), these shades facilitate interpretation for both color and non-color users. Cumulative risk can be calculated for each criterion and service/domain area.

Example

Example of a standard risk assessment from Fundamentals of Software Architecture.

Notice the accumulated risk for data integrity is the highest at 17, while availability registers the least risk at 10. Relative risk for each domain area can also be determined with customer registration posing the highest risk and order fulfillment the lowest.

These numbers offer a basis for tracking improvements or deteriorations within specific risk categories or domain areas.

In practice, not all risk analysis results are presented simultaneously. Filtering becomes imperative to convey a targeted message in a given context. For instance, in a meeting focusing on high-risk areas, filtering can spotlight only those areas, enhancing clarity and maintaining a favorable signal-to-noise ratio and presenting a clear picture of the state of the system (good or bad).

Tracking Trends: Improvement or Deterioration

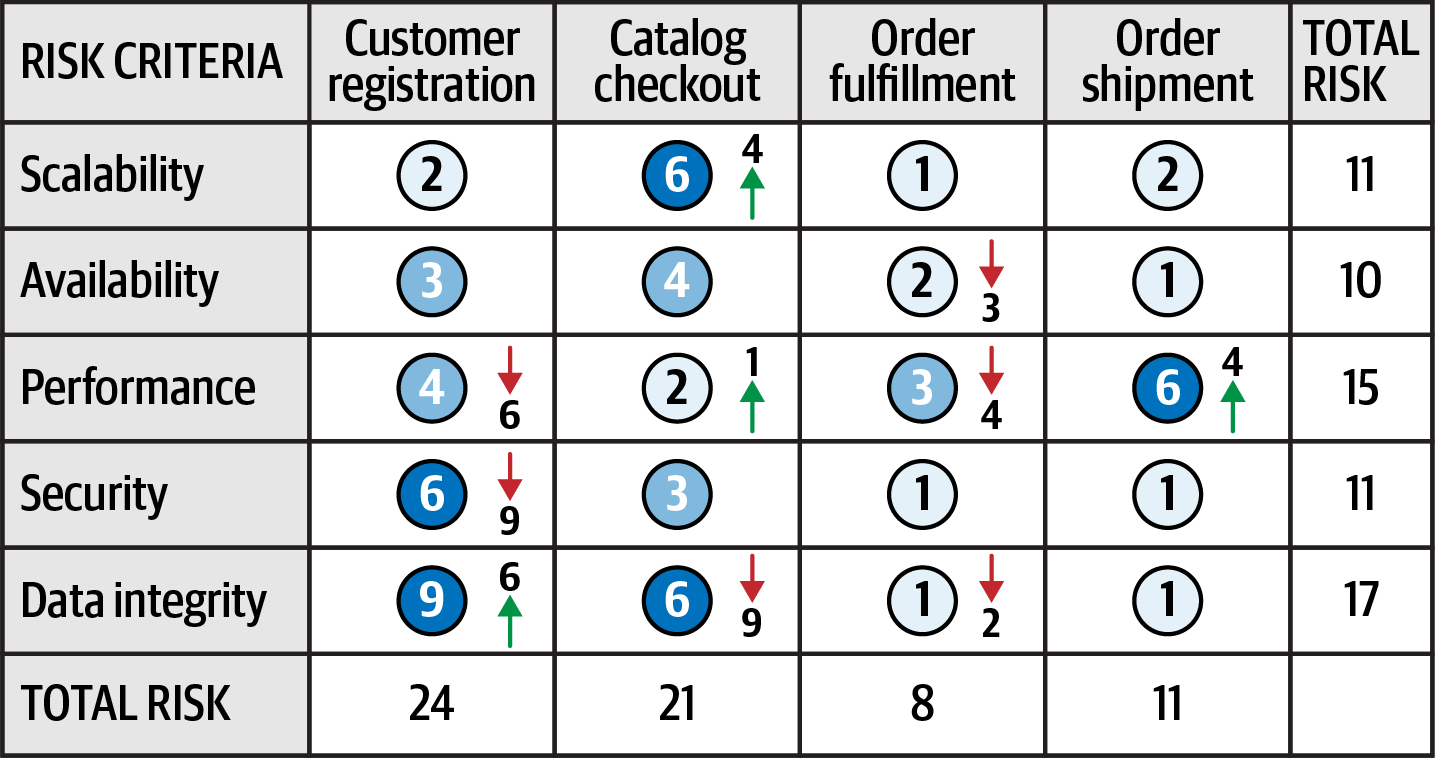

The presented assessment report offers a snapshot in time, lacking insights into whether conditions are improving or getting worse. To address this, incorporate directional indicators such as plus (+) and minus (-) signs next to the risk ratings.

Example

Showing direction of risk with plus and minus signs from Fundamentals of Software Architecture.

Examining the example, while the performance for customer registration is medium (4), the minus sign signifies a worsening trend, approaching high risk. Conversely, the high scalability rating for catalog checkout is accompanied by a plus sign, signaling improvement. Ratings without directional signs indicate stable risk conditions, neither improving nor worsening.

An Alternative Approach

Showing direction of risk with arrows and numbers from Fundamentals of Software Architecture.

Continuous measurements facilitated by fitness functions shows direction of risk, allowing for trend analysis and determining the directional trajectory of each risk factor.

Risk Storming

Risk storming plays a crucial role in assessing the overall risk of a system, ensuring that no potential areas of concern are overlooked. A single architect may not possess complete knowledge of every system aspect, making collaboration essential in this process.

Risk storming is a collaborative exercise focuses on specific dimensions of risk, such as unproven technology, performance, scalability, availability, transitive dependencies, data loss, single points of failure, and security. Engaging multiple architects, along with senior developers and tech leads, brings diverse perspectives and enhances the understanding of architectural intricacies for everyone.

The risk storming process comprises two key phases: individual and collaborative. In the individual phase, participants independently assess risk using a risk matrix, ensuring unbiased evaluations from anyone. Subsequently, in the collaborative phase, participants work together to identify consensus on risk areas, engage in discussions, and formulate effective solutions for risk mitigation.

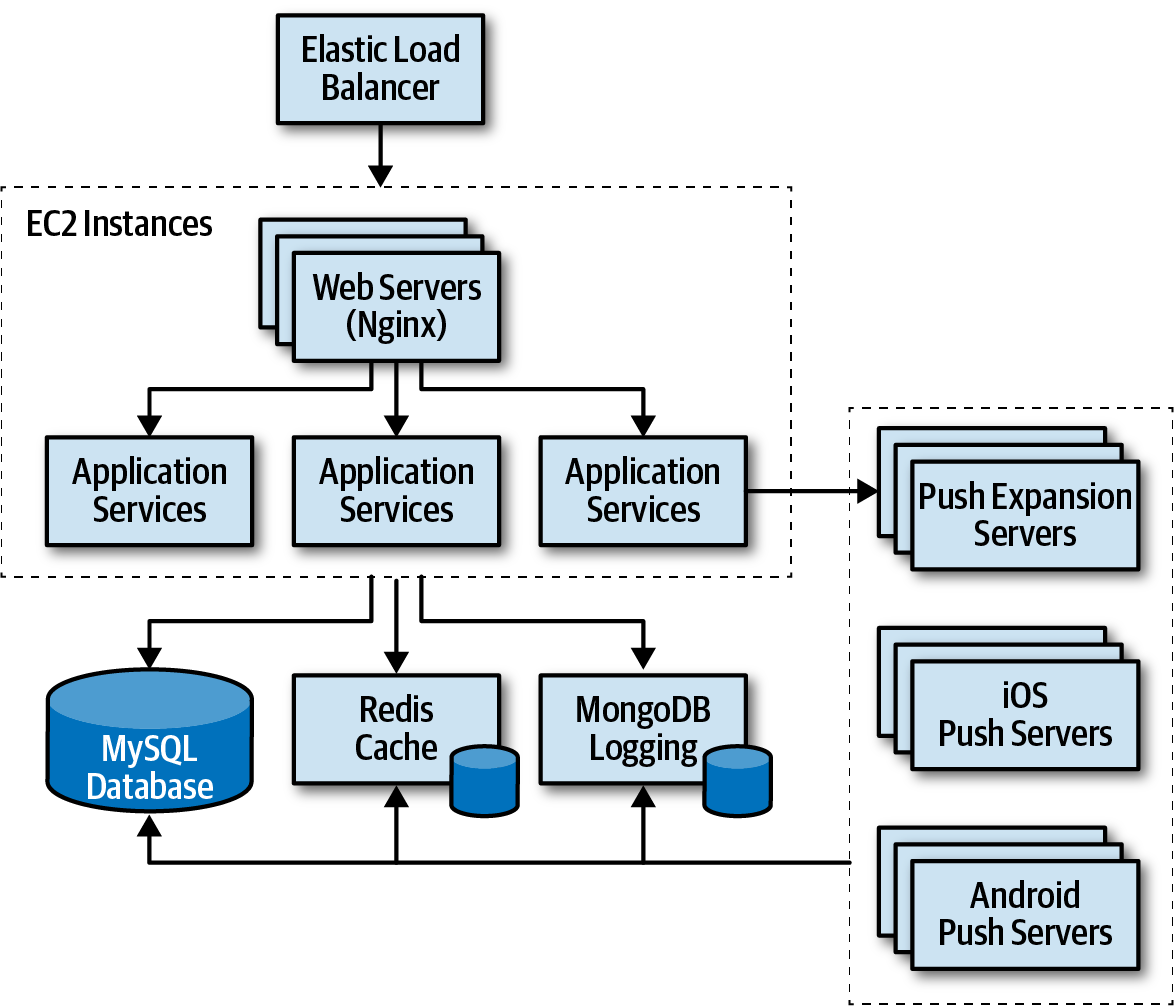

Throughout the risk storming effort, architecture diagrams are indispensable. Holistic risk assessments utilize comprehensive diagrams, while risk storming within specific application areas employs contextual diagrams. The architect is responsible for maintaining up-to-date and accessible diagrams for all participants.

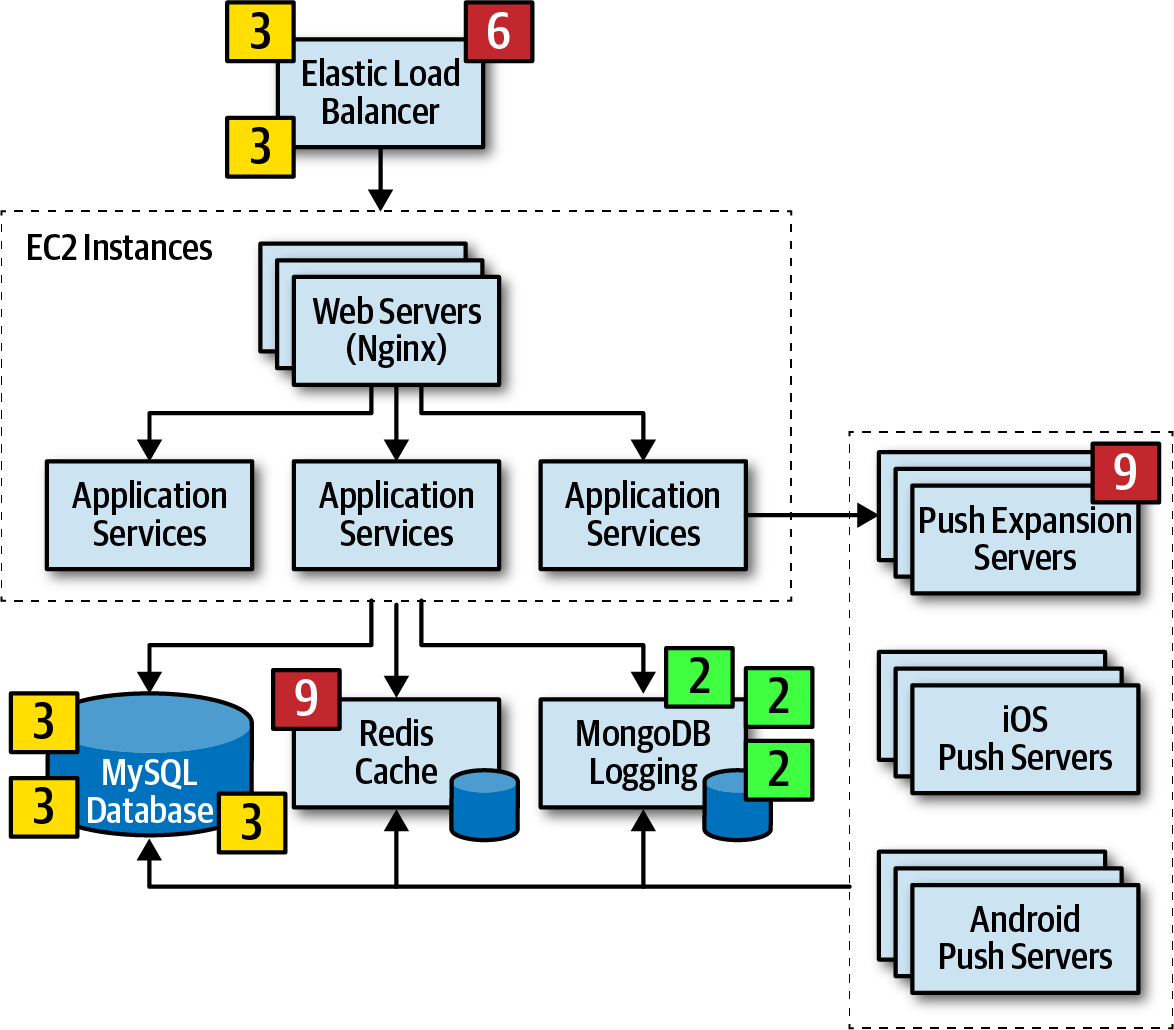

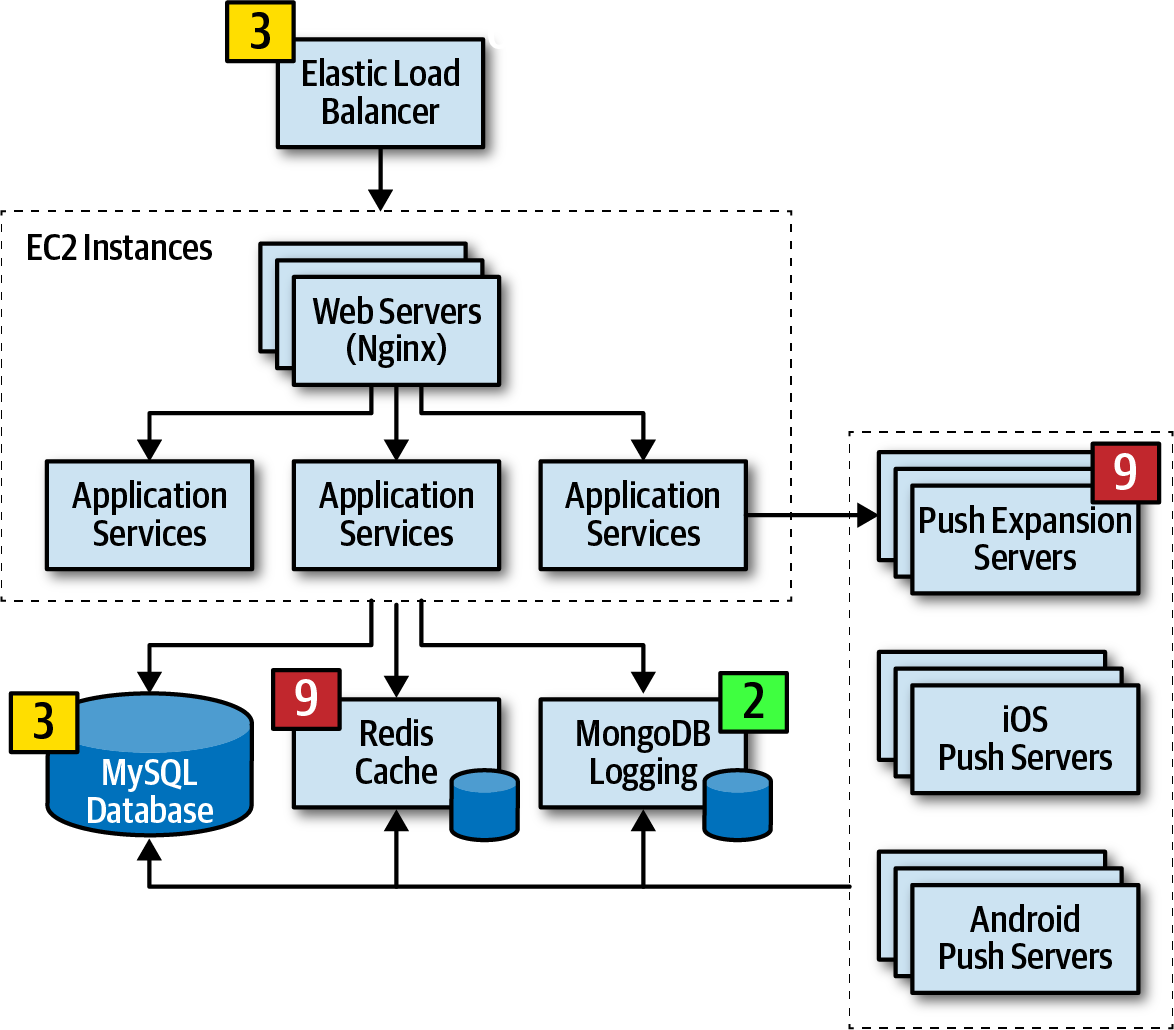

Architecture Diagram Risk

In the example, an Elastic Load Balancer, EC2 instances with web servers (Nginx), application services, MySQL database, Redis cache, MongoDB database for logging, and Push Expansion Servers. This example architecture serves to illustrate the risk storming process.

Architecture diagram for risk storming example from Fundamentals of Software Architecture.

Risk storming can be broken down into three activities:

- Identification

- Consensus

- Mitigation

Identification is always an individual, noncollaborative activity, whereas consensus and mitigation are always collaborative and involve all participants working together.

Identification

The identification phase of risk storming is a crucial step where participants individually pinpoint areas of risk within the architecture. Here's a breakdown of the identification process:

Prepartion and Invitation

- The architect leading the risk storming sends invitations one to two days in advance of the collaborative session.

The invitation includes the architecture diagram (or link) and specifies the risk storming dimension to be analyzed.

Individual Analysis

- Using the risk matrix, participants autonomously assess the architecture, categorizing risk as low (1-2), medium (3-4), or high (6-9).

Post-It Note Preparation

- Participants prepare

small Post-it notes, each representing an identified risk area, with colors indicating the risk level (green for low, yellow for medium, and red for high).

It's common for a risk storming session to focus on a single dimension (e.g., performance), but occasionally, due to resource availability or timing constraints, multiple dimensions may be analyzed simultaneously (e.g., performance, scalability, and data loss).

Tip

However, whenever feasible, it's advisable to limit risk storming efforts to a single dimension. This ensures participants concentrate on specific aspects, preventing confusion regarding multiple risks identified for the same area of the architecture.

Consensus

The consensus-building phase in the risk storming is a collaborative effort aimed at achieving agreement among all participants regarding the identified risks within the architecture.

Upon commencement of the risk storming session, participants affix their Post-it notes onto the architecture diagram, marking areas where they individually identified risks.

Once all Post-it notes are in place, the collaborative aspect of risk storming initiates. The team collectively examines the risk areas, striving to reach a consensus on risk qualification. If an item receives unanimous agreement in terms of risk level, no further discussion is necessary. Items with divergent results prompt discussion. Individuals with varying assessments must elucidate their perspectives. In cases where everyone provides different ratings, a comprehensive discussion is required. Following the discussion, a consensus must be reached.

Mitigation

Following unanimous agreement among participants regarding the qualification of risk areas in the architecture, the subsequent and crucial phase is risk mitigation. Mitigating risk in architecture often necessitates alterations or enhancements to specific areas that might have initially been considered flawless.

This typically collaborative activity explores ways to diminish or eradicate the identified risks. Mitigation efforts can range from comprehensive architectural changes prompted by risk identification to more straightforward refactoring, such as introducing a queue to alleviate throughput bottleneck issues. While these changes enhance the architecture, they usually come with additional costs.

Cost Negotiation Example

Key stakeholders play a pivotal role in determining whether the incurred cost justifies the risk reduction.

For instance, suppose a risk storming session identifies the central database as a medium risk (4) for overall system availability. Participants may propose clustering the database and dividing it into separate physical databases to mitigate the risk, albeit at a cost of $20,000. A negotiation ensues between the architect and key business stakeholders, where the stakeholders ultimately decide the cost outweighs the risk. In response, the architect suggests an alternative approach—skipping clustering and opting for a two-part database split, reducing the cost to $8,000 while still mitigating most of the risk. In this case, the stakeholders find the compromise acceptable.

This scenario illustrates how risk storming not only influences the architecture but also impacts negotiations between architects and business stakeholders. Risk storming, coupled with the risk assessments, proves to be a valuable method for identifying and monitoring risk, enhancing architecture, and facilitating negotiations among key stakeholders.